|

|

|

On the Buses ~ Early days

It seems to have been the

mainstay of my early life, that somehow, in one place or another, at

sometime or other, I always seem to have been on a bus, or trying to

catch one, or to have just missed one.

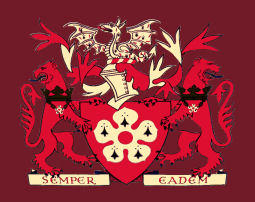

Being a Leicestershire lad, the colours of those buses were mainly of two sorts: the deep crimson of the "Friendly Midland Red", and the even deeper maroon and cream, of Leicester City Transport. For the first few years of my life in the county, my boyhood passenger experience was largely of the former. Mum and Dad were from Coalville and Coleorton, and so it was that area that I first got to know well. Dad also had relatives in Leicester and so the occasional visit to that city made for a change of scene - and livery. This was the term that I discovered, much later in life, was the correct way to describe the paint job on coachwork; whether on a humble van, tram, train, or even a jumbo jet. But for me, as for most kids then, journeys largely meant buses, and every bus journey was an adventure, no matter what the colour of the bus. I cannot recall a time when I was NOT aware of the smart, gold logo, and of how the name had larger letters at the beginning and at the end. Equally smart was the City Transport crest, a five-petal cream flower on a red shield, with its red lion supporters, and some funny, foreign words I didn't understand, all on the shiny, deep maroon background body colour of the whole bus.  I would be a much older schoolboy before I learnt that the flower is a cinque-foil, and the words are the city's motto - Semper Eadem - meaning Always the Same. But I knew nothing then of the history behind those colours and logos. It would be years before I understood the significance of the City Transport's 'Corporation' colours, and the coincidence of the colours of the coaches on the trains of the LMS. Or that the Midland Red was properly the 'BMMO', as it confusingly appeared in all their timetables. But, the 'Birmingham & Midland Motor Omnibus Company' was rather a mouthful, for anyone, let alone an eight-year-old. The 'Friendly Midland Red' had my vote in those latent days of the mid-1950s through to the early 60s, not least because of the thoughtful notice displayed on the platform, positioned to catch everyone's eye just before alighting. Nobody ever "got off" a bus in those days; one 'alighted.' And just before one alighted, this notice hit you between the eyes, right above the doors. It simply asked, in large, gold letters on dark red:

Have You Forgotten Anything ?

The question mark was especially large, so large if it had fallen off and hit you on the head, it would have hurt. My mother always seemed to think that it was there just for her, to remind her as to whether she had forgotten us, that is, myself and my little brother. She often threatened to 'forget' us - or wished she could. Well, she did occasionally mislay us. She lost me in Woolworth's in Gallowtree Gate on one occasion! I shared a mug of tea and a biscuit with a very nice police sergeant in a big white building at the top end of Charles Street until, like the 5-year-old piece of lost property I was, I was eventually reclaimed. That notice on the platform of all those Red buses haunts me still. It only occurs now that perhaps mum really was tempted to 'lose' us on a Midland Red bus, or any bus, if only for a night or two. I could at least have had a night in the depot. And she could always reclaim us. If not, well, I knew the routes, so I'd find my own way home! Leicester Transport buses merely had an official notice warning about the financial perils of being a filthy sod and spitting on the floor, and reminding folks that no more than five persons were allowed to stand in the gangway. Another reason the Midland seemed nicer to us kids was that they were warmer. And I should think so too, with those nice, big, folding platform doors. Leicester Transport buses didn't have platform doors. They didn't have any doors! They didn't seem to mind how cold their passengers got, or if they sometimes accidentally fell off. Or so it seemed to a young lad. GOING TO GRANDMA'S Leicester to Coalville For some reason, journeys to and from Coalville always seem to have been winter ones in my memory. If it was raining or drizzling when leaving St Margaret's, it would be sure to be snowing by the time we reached Markfield. Of course, I know now that this was because that latter place was much higher up, "on the Forest." Indeed, almost as soon as one left the city, after traversing Sanvey Gate, under those hugely imposing girders of the Great Central Railway, across the amusingly named Frog Island (where I never saw one, single frog), one seemed to be climbing all the way. The climb proper commenced at Groby Road/Fosse Road corner, and then Groby Road just went up and up and up. Then it was up and down all the way to the Field Head - but generally up. After that, there were still ups and downs all the way to Coalville - but generally down.  Leicester Transport buses seemed to be somehow noisier, whereas the Midland Red seemed to have a nice, soothing whine to their engines, almost a song-like drone that a little boy could fall asleep to. But I never fell asleep because every journey was an adventure. Though not every bus journey we took was on the Midland Red or the maroon Leicester Transport.  Dad was then in the RAF, at Grantham, in the 1950s, and so we invariably travelled to and fro into Leicester on a deep green and cream bus, a most odd-looking bus, belonging to another company with another mouthful of a name, the "Lincolnshire Road Car Company." An odd name as well, because it was most definitely a bus, not a car. It would be nearly another twenty years before I knew that the term 'car' was a hangover from the days of the tram car. But, they did have queer looking buses, and with very odd seating arrangements upstairs. Odd to me, of course, but not to any native of Lincolnshire or East Anglia, or anywhere else where Bristol Lodekkas were king. In 1950s rural England, if it were a country bus, and painted green, it was usually a Bristol - and more often than not by then, a Lodekka. GRANTHAM to LEICESTER 26 miles of peculiar names The up and down rolling journey from Grantham into Leicester was yet another adventure, and to both my parents, probably a great embarrassment, for my brother and I drove that Service 25 all the way, fighting to be first upstairs to gain the front, right-hand seat over the driver. Imagination made for great steering wheels in those days, and we had one each! The names of places on that journey seem now to chime on the bells of memory: Harlaxton, Denton, and Croxton Kerrial. An odd name that last one, and they never said it properly. The conductor always put on a right posh accent and announced it as 'Crowson' Kerrial. Besides, what was wrong with the 'x'? We used to wait a few minutes there, and if we were lucky, we'd see someone drawing water from the huge village pump right by the bus stop. No small pump, that. It could have filled a railway engine! I wonder if it's still there. If you looked back, as you climbed away steeply from the village towards Melton, a clear day would reveal the misty silhouette of Belvoir Castle atop its distant hill; the return journey view was even better. The next stop was Waltham on the Wolds, and then almost all downhill into Melton Mowbray. A funny county, this place of my heritage. Such long-winded names, and often spelt incorrectly, that is, to an impressionable eight-year-old trying to get to grips with his own language. There were so many letters that were just ignored. Melton nearly always seemed to be holding a market, which caused no end of extra hold-ups and muttered curses from our Dad. He never liked markets, but I think Mum wouldn't have minded hopping off (sorry - alighting) for a quick look round. It was a still a little up and down after Melton, through Kirby Bellars. "Look, there's another one of those posh, long names." Presently we were down to a far more gentle drop into Syston. In winter, and sometimes spring, the whole of the valley that dropped away down to the right of the Leicester road would be awash with flood water - an extended River Wreake - and miles and miles of submerged fields, with only trees and hedge tops showing under a pale reflection of a watery sky. It always seemed wet, and damp, about now - "Yes," my mother would say, "we're coming into Leicester alright! Always Damp!" According to my dad, that should have been the city's motto, 'Semper Damp." It was somewhere near here, just before Syston, that I have a very distant memory of seeing two smoking steam engines in a field - one at one end, and one at the other. I would be over forty years old before I realised that what I had witnessed were the end days of steam-ploughing, drawing the plough on a long cable up and down the field between two smoking engines. The day of the horse was numbered even then. The roads were busier now, many more cars, and lots of lorries and vans. And of course, the occasional bus, usually a red one. Syston gave way to Thurmaston, and before we knew it, we seemed to be flying down our first real dual-carriageway. 'Flying' is a relative term here; we were on a Bristol Lodekka. We weren't used to dual-carriageways in Lincolnshire! Even the A1 wasn't duelled everywhere back then. 'MEL-ton Turn', shouted the conductor, as we made more and more stops, and now there were buses everywhere, mostly maroon and cream. 'BEL-grave Station,' he'd shout, and finally, a few minutes later, we'd turn into St Margaret's, where there were more buses than you could shake a stick at. And joy of joys, most of them were red! There, reluctantly, we small boys had to alight from our green bus, but only to go on another bus. And so another minor question bedevilled a small boy; if it was called St Margaret's, why did everyone seem to insist on calling it Sandiacre Street. SO MANY CHOICES Red buses - Brown buses - Blue Buses Which bus we caught next would depend on which relative we were going to visit first. If it were Dad's city relatives, then it would often be a cold and noisy, maroon and cream bus of the Corporation - with no doors! If we were going on to Coalville, to our maternal grandparents, "Over 'ome," as Mum said, it would be a warm Midland Red. In which case, it was literally a case of jump off one bus and on to another. With a bit of luck our bus would be already in, and we wouldn't be left waiting by those long, modern tubular-concrete bus shelters. Draughty, mum called them. Huh! They seemed to be an improvement on everywhere else I'd been, especially those places that had NO bus shelters at all. Grantham's bus station was nothing to write home about. You could run about in St Margaret's shelters; the echo of boyish shouts and laughter was tremendous in those concrete tunnels. In retrospect, they were like long miniature aircraft hangars, but veritable wind tunnels on a bad day. But if we were to go and see Mum's sister first, at Newbold Verdon - there's another posh name again - we would sometimes have to catch a bus of a much different colour. Even if the name of this bus was a right contradiction in terms - 'Brown's Blue' - as if it couldn't seem to make its mind up as to what colour it wanted to be. But that wasn't often. Usually, it meant the longest traipse of my young life, right across the city. And this often at the trot because connections were always tight, down to somewhere called "The Newarkes," or sometimes to catch not a Brown's Blue but another Midland Red - down near the canal. And at sometime, I recall Newbold buses leaving from 'Western Boulevard,' practically IN the canal. God help us lads if we missed it. What a Stupid Arrangement, mum cursed. They were ALL Midland Red buses, why couldn't they ALL depart from the same damned place! It was just the same if we were going to Dad's Grandma's, right out at Great Glen. We practically had to run all the way up Charles Street to Northampton Square. I used to think I'd ran all the way to Northampton itself! And I don't dare guess what it was like for my brother - his legs were shorter than mine - he was only four. A funny term that, to 'catch' a bus. But one learnt as one got older, that it was entirely appropriate. You did have to catch the damned things, sometimes by stepping out into the road and trying to get hold of it with both arms! Or so it seemed. For the unwary intending passenger, an approaching bus took some stopping at times. One never felt as if it stopped willingly. One got the impression from the look of the driver that it was something of a chore to stop and pick up passengers. Leicester Transport buses seemed even less willing to stop and to allow one to alight. For they didn't always stop - not properly, wheels motionless. It still moved, just, and one had to be very nimble before that blessed great bell clanged and it was out of sight! And you with it - but only if you were very quick! Occasionally, though rarely, if we had missed the bus to Coalville, or connections were difficult, it would involve an even longer run - right up Granby Street, to London Road Station. We were going on the train - wonderful! I never seemed to have time to look at all the posters as we were dragged across that great bridge across the platforms - we always seemed to be running. And those long, wide stairs down to the platforms themselves - absolute murder if one's mother had recently purchased yet another baby brother from Baby Kingdom, he who rode in total luxury in a push-chair, being pushed at near-light speeds. Me being the eldest, and the tallest, I had to carry half of him and his chair, sideways on, with mum holding on to her bags as well, as we fairly tripped and skipped down to our now-moving train. We were always late! But the train journey - in contrast to the bus - well now, that was another treat! TO COALVILLE AGAIN and more crazy names But as often as not, we would be going on to 'Co'ville', as my mother called her birthplace, so once into St Margaret's, it was all aboard the 669, showing Ashby-de-la-Zouch. Crumbs! Some of these names are unbelievable. Do they get any dafter! All my life, it seems I've been a bit of a collector of names, and there's no better place to see names of all kinds - odd names, queer names, rude names even, than on bus destination blinds. Rude? No? Then what about GriffyDAM! That was rude, wasn't it? It was in the 1950s. If I ever so much as breathed the word, 'damn', on it's own, in a sentence not connected to water, and in my parent's hearing, I got my ear well and truly clipped. And why were they called blinds, anyway? Having rushed all of the 100 yards from where the Grantham Service 25 dropped us, to the right stand where the Ashby 669 departed from (or was there a 665 just to Coalville?), we would often sit at least a quarter of an hour atop a freezing cold red double-decker. My guess is, that was back then either a D5 or a D7. Atop, because us lads still wanted to drive, and freezing because the engine had been stopped for at least an hour and the engine is what made the heaters work. Mum explained all this basic science. Of course, regulars on that route would know that all we were waiting for were the crew to finish their tea. Just when we all thought we would have to get off and go home to bed, a likely couple of chaps would emerge from the central canteen, shaking the last drops out of large, white enamel mugs. Eventually, we'd feel the bus move and groan on its springs. The cab door would be heard to open - the bus would move slightly, and then the door slam shut with a hollow bang. We'd hear the conductor remove his ticket machine from his tin box, and then stow said box in some secret cubby hole under the stairs. At last, movement! "Are we going now, Mum?" The engine coughs, coughs again, and reluctantly fires. Another moment, a shout perhaps to a late passenger - an increase in revs from the engine. The driver is ready. Then " burp-burp " goes the buzzer. We hear the doors whine shut. The revs drop to a rough tick-over, the bus jolts slightly as it clunks into gear, and we slowly, slowly, slowly start to move, almost in a series of little lurches. In fact, we not so much moved, as lurched, from one little bit of the road to another. Hurray! At last - we're off. Off we set, past St Margaret's fine church, left into Sanvey Gate, right into Northgates and under a huge railway bridge, over Frog Island, out through the traffic and slowly on towards the massive Groby Road junction. How did the driver know which way to go to get there? Up, up, up Groby Road, past the Fever Hospital, and then Gilroes. Conveniently placed for a cemetery I always thought, that is, after Mum explained just what the Fever Hospital was for. The engine and gearbox would whine and grind its way slowly - it always seemed to be slowly - up yet another hill. First Groby, then, colder and colder, we approach Markfield and the Field Head. The windows would be well steamed up by now. We'd make a circle with our sleeve and elbow in the condensation as it got harder and harder to see out. The bus lurches into the lay-by, and the doors whine open to drop someone off or perhaps pick up some poor, shivering soul. There's a sudden temperature drop at the front upstairs. And we wait - wait for about 5 minutes. Brrr!! Then, moving again, slowly, oh so slowly, on to The Flying Horse - another pub. Another lay-by. Another wait. We wait again. "That's what we could do with," opines Mum, looking at the name over the pub, "it'd be quicker than this blasted bus!" The great mass of Bardon Hill looms in the mist on the right, with its huge radio masts on top, and if we were lucky, we'd get caught at the railway crossing just down from another pub, 'The Birch Tree'. Held up again - by dozens of wagons that went on for ever, trundling out of Bardon Quarry loaded with fresh stone. Being lads, we'd drive everyone else upstairs totally nuts as we counted them. Mum always told us that we'd come by there one day, and Bardon Hill would be gone, vanished forever. Speeding up now, we'd glide and whine down Bardon Road and on into Coalville, stopping to let folks off here and there along the way, to drop off (whoops! I mean, alight) just inside Ashby Road, almost outside the fish and chip shop opposite the Clock Tower. We would alight there only if we were going to mum's family down Highfield Street. But if we were going to dad's family first, we'd stay aboard and go on to Coleorton Cross Roads, the bus itself then going on to Ashby. If we were really lucky, our bus would be a slightly different number, and go a different way, first to Sinope then right down Coleorton Moor itself to where we really wanted to be, dropped off near the Angel Inn - but only "by request" - if you please - and if we were really lucky and the driver knew us, he'd drop us right outside grandad and grandma's cottage. Our family must have been famous in the village in those days, it's still called 'Haywood's Cottage' even now. If we were bound for Highfield Street and our other grandad, Grandad Holt, once again, time was of the essence. Oh no! Time for another mad dash with push-chair and brothers and bags n' all. This time to rocket down Belvoir Road to Marlborough Square to catch a single-deck bus for Standard Hill - on another Midland Red.  'Catch' again being

the operative word here. If we missed it, it could be because we'd been

caught at yet another railway crossing. This time it was the spur that

led from the main Leicester to Coalville-Burton line down into the depths of

Snibston Pit; but, as often as not, the crossing gates on Belvoir Road

would be open to us and to traffic, even if there was a great big

snivelling, steaming monster waiting just beyond the gates to haul a

long train of coal wagons away to the boilers of the world. "Er, is it

coming to get me, Mum?" I'd say, pausing a moment to look in

self-inflicted terror and wonder at the blackened monster (calm down, it's only a tank

engine!) spewing steam and water everywhere. 'Catch' again being

the operative word here. If we missed it, it could be because we'd been

caught at yet another railway crossing. This time it was the spur that

led from the main Leicester to Coalville-Burton line down into the depths of

Snibston Pit; but, as often as not, the crossing gates on Belvoir Road

would be open to us and to traffic, even if there was a great big

snivelling, steaming monster waiting just beyond the gates to haul a

long train of coal wagons away to the boilers of the world. "Er, is it

coming to get me, Mum?" I'd say, pausing a moment to look in

self-inflicted terror and wonder at the blackened monster (calm down, it's only a tank

engine!) spewing steam and water everywhere. "Stop messing about, an' urry up, or we'll miss another blasted bus!" would be my mother's answer, as my arm would be almost wrenched out my shoulder. But we usually missed it, and had to walk. Woe betide Grandma if she hadn't got the kettle on by the time we rounded the bend in Highfield Street, up by the Co-op. It was usually gone tea-time - and raining. I always used to wonder why women in those days used to soak their feet when they were already wet. OH, TO BE IN COLEORTON or down the pit To go on to Coleorton, on the 667 or 669, would involve two more small parts to our adventure. Locally, it was pronounced C'lorton. If anyone asked a conductor for a ticket to Cole-orton, he would have been met with a blank gaze - Foreigner! Though, historically, the two parts of the name did use to be written separately. And yes, it was one of the first places in the county where coal would be commercially dug, hence the name, and so close to the surface that it didn't need to be mined in the modern sense. They could almost collect it in buckets. But first, we would have to pass the Midland Red Bus Depot, just down Ashby Road and just before the pit. It seemed there were nearly as many buses in there as there were in Sandiacre Street in Leicester. Some of them were right old bangers 'n all. Occasionally we might see one actually being washed, but usually they were all asleep. Then, we'd pass the Pit, Snibston Pit, known locally as Snibby. If we were lucky, we'd see the pithead wheels turning. Sometimes, there'd be dozens and dozens of grimy-faced miners pouring out the pit gates, and across the busy road, going I knew not where back then. I never knew, until only recently, where all these men were actually going. An elderly uncle recently enshrined the scene in verse, and explained to me how the men all had to pay for the building of the pit-head baths themselves - a penny a week out of their own, very meagre wages! Also, how the Coal Company owners had been too mean to grant any land within the pit premises; as a result, making it necessary for the several-times-daily mad dash across Ashby Road for each finishing shift to get a little clean before going home. I feel the verses are worthy of inclusion here. Do they chime the memory gongs for you? Snibston Colliery ~ Coalville,

Leicestershire But on with the journey --   On the Buses On the Buses ~ A Temporary Job? I have always counted myself a very fortunate chap. Fortunate in that my career as a busman, such as it was, started at a time when it may be said that we were just seeing the last glowing embers of a dying age. That sounds as if it were long, long ago. But it was not so very long ago, even if it was in the last century. And this is how it all appeared to me at the time. The dying age to which I was a first-hand witness was that of the now-lost principle of mass public transport affordable for all. The heyday of the bus conductor was all but numbered. Bus design would soon be turned on its head giving a whole new look. I learnt my trade on buses that had the engine in the proper place - at the front! In the mid to late 1960's, there were still plenty of staff in all industries who had served in the forces during the wars. Some senior men close to retirement in the 1960s had been young men in their teens at the front in the First War. Men who had fought and suffered, who had both known and dispensed discipline, and who still had pride in whatever they did. The general public were still basically a decent, honest folk, the majority of which, would no sooner diddle a corporation bus conductor, or the corporation, than fly in the air. Traffic was getting worse, and in some cities, almost at a stranglehold. But new technology was coming through to win the battle against the motorcar and the even newer battles against the vandals, drunks and late-night troublemakers. In general, there was an air of quiet optimism, which in retrospect, we can see was greatly misplaced. The comfortable and seemingly secure industry that I came to know so well was, not so many years later, to undergo a shake-up that can now only be described as wholesale rape. A strong and emotive phrase to use, but when one thinks of the countless people who have been hurt, financially and socially, by that industry's sole concern with short-term profit, backed up by heartless and soul-less government, it is a term I feel justified in using. But I was never known for holding back in my condemnation of the dismantling of an essential public service that still had so much to give - and is needed ever more now. I suppose it could be said that buses were 'in my blood,' almost a genetic sort of inheritance that I was in some way predestined for. But such an idea only now occurs in retrospect, that wistful act of looking back and wondering at what might have been. If buses seemed to be 'in my blood,' then so too was coal-mining. So why didn't I become a miner? A lot of what I know now, I didn't know then, back in the mid-sixties, as a lanky youth, just out of school with only one aim in life. I knew that one grandfather had been a miner, but it would be nearly thirty years before I discovered that that was also true at one time of my other grandfather. And the family pedigree for transport, if it can be called that, was in fact rooted in trains and trams, not buses. Curiously, I did not become even remotely interested in trams for a long, long while, again, almost thirty years and long after they were consigned to the museum and historic postcards. I did have an uncle who was a conductor on the Midland Red at Coalville, and as a small boy, I had even lived in a bus for a while - albeit a magnificent six-wheel trolleybus - ex-Newcastle, I think. That bus was my home for a couple of years during my father's time in the RAF. Married quarters were in short supply in the early 1950s, and some personnel were allowed to buy their own caravan, which the RAF would site on camp, all connected to water and mains electricity. My dad simply bought this old green trolleybus, and converted it into a home. I recall it being fun to live in and very comfortable. So, if it was my destiny to become a busman, how was it that it all occurred purely by accident, almost on a whim? I was very given to whims in those days. My one aim in life was the result of another whim: to be a sailor. Not just any sailor; not a merchant sailor or any old tar, but a Royal Navy sailor. I had set my heart on going to sea, on joining the Royal Navy, since the age of about 12 or 13. Buses could not have been further from my thoughts. I still muse on how it could come about that I could fail the medical for the Royal Navy on account of having rheumatic fever aged 11 (and consequently a suspected dicky heart), yet later pass a medical to drive a full bus of 80 trusting Leicester passengers. Reasons are still beyond me. But I did. They must have been desperate. And indeed they were! For those not familiar with those times, the mid-to-late sixties in the English Midlands was a time of plenty for most people. Jobs were so abundant that there was simply no excuse not to work. Since starting work as a shoe salesman in the Coalville Co-op, I had had no less than 10 jobs, not counting the last one which didn't count because it was a fraud - more on that later. Each time I changed job, it was for a little more money somewhere else. Youngsters like me simply walked from one job to another, as if we were changing shirts, with an ease and aplomb that today's youth may find hard to credit. The Midland dole queues were made up largely of a mixture of people who couldn't work, because of some illness or disability, and those who simply would not work for any number of nefarious reasons, usually bone idleness. It was different, even then of course, in other parts of the country, where there were still serious shortages of real jobs, but this was definitely not the case then in my native Leicester and Coalville. It had been bad, 30 years before in the 1930s, but a young fit lad like me had no excuse, non at all, not to work back in 1965. Had there been one, I'd have found it. For those that wanted a job, all you needed was a late edition of the Leicester Mercury , and the world was your oyster - jobs galore, in almost every industry. Boot and Shoe manufacture and retailing, knitwear and hosiery, printing and machine tools, heavy and light engineering, of every sort. Just about everything except shipbuilding and deep-sea fishing! And yes, if you wanted to travel just 10 or 12 miles out of Leicester, there was mining too, and just at a time when that industry was getting both safer and very hi-tech. So what with trams in the family past, and buses in the family present, dad was keen that I didn't get any more involved with buses than with mining. He was very put out when the very first job I lighted on in the paper, and fancied enough to apply for, was as a 'battery-hand' in the Midland Red depot in Ashby Road. In fact, he went almost ballistic, to use a modern term. Wouldn't allow it. "No son of mine is going to work humping blooming great bus batteries around. Forget it." So I looked again, and went to work, not in overalls, but in a suit and collar and tie, two days after my 15th birthday, at the Coalville Co-operative selling shoes instead. Not much of an improvement, but at least it was clean - and safe. And thereby buses were put out of my mind. And would remain so for just about the next three years. From the Coalville Co-op to Leicester Co-op, to Timpsons Shoes and Benson's Shoes, to Marshalls & Snelgroves and thence Lewis' and on to Simpkin & James. If I was not to be allowed to join the RN, I then nurtured some forlorn half-dream of pursuing a career in shop management, but my heart was not really in it. Shoes, soft furnishings, art and graphics work, food and produce, I tried them all. And jobs all to be found nightly in the pages of the Leicester Mercury, including the one as a photographer's assistant that turned out to be a total three-week fraudulent con. That was my last job before the buses, except, it wasn't a job, if you see what I mean. Today it would have been a police matter, but then, the conmen themselves disappeared back into the woodwork of London, owing hundreds in wages and hotel fees, and now't more was said. I was well taken in. Moreover, my mother would throw a veritable duck fit if I went home without a job at all. And so, now finding myself out of work that day for the very first time, and ambling dejectedly in the general direction of the dole office that sunny October morning, it was in Humberstone Gate that I espied a faded notice in the little front-office window of Leicester City Transport: "Conductors Wanted." It was faded because it had been there a long time, perhaps 30 years, standing on a small wooden easel, like a sad appeal for help. An appeal because conductors were always wanted; the pay and conditions were so poor that staff were traditionally hard to come by in the first place, and even harder to keep for any length of time. Having just turned 18 only eight weeks previously, and with no idea of the real pitfalls of the job, but a sort of fondness for buses, in I went - like a lamb to the slaughter! Well, it was only going to be a temporary job, just to tide me over. Mostly to pacify my mother, but otherwise, just till something else turned up, you understand. Isn't that how we all started? From One Job To Another Just what was it that made me walk through the City Transport's Humberstone Gate front office door on that sunny day in October of 1968. I've often thought back and tried to recall the moment. Memory is often more driven by retrospect, and coloured by the ensuing experience, than by pure recall - and so it may be in this case. And I conclude it was pure fate. Chance. Had I walked through the city a different way, and not past that office, my life almost certainly, would have taken a different course. But I do vaguely remember the feeling of being such an utter bloody chump to have given up a perfectly good job in a cheese shop (where indeed my future wife still worked) for a spurious job that had turned out to be no more than a fraudulent con. In addition, one effect would be the inevitable tongue-lashing from my mother the moment I walked into the house, just turned 18, and now designated as unemployed. She had warned me, had a sixth sense about that stupid photography job. So I had to get a job, must get a job, and be quick about it. I just dare not go home without one. Besides, I actually fancied working on the buses. I had a hazy idea that it would involve shifts, but didn't really know what this would entail back then. So the answer to the question, what made me stop, and walk through that door? Simply because I just happened to be walking past. I only then had a vague notion of my family history's involvement with trams, and it didn't seem like fate at the time. Unexplainable, it just happened that way, as chance often does. The uniformed inspector behind the enquiry desk looked as most bus inspectors did in those days - like a policeman. He directed me upstairs to where I would please fill out an application form and sit a small test of writing, and adding up. To my intense surprise, knowing my own dislike and ineptitude at the latter, I passed. I could write for England, but couldn't add up for gum drops - but I did it that day. It was a simple task, such as if I sold 480 tickets at a penny each, how much would I have taken, and similarly for 3d, and then a tanner, and so on. Normally, columns of figures misted my eyes over and I'd go into a dizzy fuzz. But I had been working in shops, and even though the adding up had been done mainly on tills, I had a lot of recent practice of adding up in my head. And the inspector seemed pleased too - but he would! Fresh, green platform staff were hard to get, and they didn't come much fresher and greener than me! I was so green I was almost white, if you get my drift. He must have been on some sort of a cash bonus to sign up native boys like me. Having ascertained that I was available for an almost immediate start, I was given clear and enthusiastic instructions; report to the Leicester City Transport conducting school at Abbey Park Road Depot the following Monday, at 9 a.m. sharp. Don't be late, lad. Thinking back, I can almost see him in my mind's eye, rubbing his hands as I left the office. A lamb to the slaughter indeed! A new boy. Just turned 18. Could speak clear English and was obviously enthusiastic. As pale and as innocent as the driven snow. Could write and add up too!. What was not to love? A LATE START! The start day in question just happened to be Trafalgar Day, 21st October, an historic red-letter day for a lad so keen on the Navy, and just as significant a day for me too. I crossed the city from Saffron Lane, having paid my fare on a Corporation bus for very the last time, and arrived at Abbey Park Road, breathless, at 9.15 a.m, already fifteen minutes late, to find the class already started. This was a bad omen, one that seemed to plague the rest of my time on buses, until I acquired a really reliable alarm device, widely and commonly known as a wife! Getting up of a morning had never been my strong point, and now there would be times when it would be a real bind. When I had first told my mother I'd been and got a job as a conductor on the buses, she almost had a fit with laughing. Not the response I had expected, though strong words were said regarding the idiocy of leaving a safe job in a shop that paid nine quid a week for the fraudulent job that paid nothing at all. I could consider my 18yr-old ears metaphorically well and truly boxed. For mum knew, as mums of lads know everywhere, how their sons are prone to lying a-bed of a morning. I'd had trouble with 8am starts in a shop, so she didn't give a hoot for my chances as a busman. Many members of the public in those days held a common belief about people in jobs in the public eye such as milkmen and busmen. A belief that they were all cheerful, early risers who just threw themselves into their work at the crack of dawn or the rising of the lark. Nothing could be further from the truth with me. I was neither a natural early riser, nor all that cheerful much before lunchtime. In our times, when the day of the conductor seems so long ago, it has become fashionable to bemoan their passing with the assumption that all were efficient, cheerful and honest collectors of the corporation's dues. Always ready with a joke, and a ready arm to collect up some struggling young mother and her waifs from the pavement. I know I was honest, I hope I was mostly cheerful, but as for the cheerful early rising bit, and much of the rest, I was to turn out to be less than average, and a lot less than perfect. There would be many times when my feelings for the job were more of a love-hate relationship. CONDUCTING SCHOOL The training school inspector was an Inspector Johnson; one of the old school of professional busmen who knew his job inside out and taught it thoroughly. No stone was left unturned, no rule of the road, or aspect of the Passenger Transport Act of 1933, was left uncovered. This is what I meant in my opening when I said that I was fortunate to have caught the last of the old days. Of course, I didn't realise or appreciate this fact then. If I had, I would have taken lots and lots of photographs, and much better than the poor offerings on these pages. The likes of me had yet to learn the job before we could be any judge of how much it would change in the future, or what indeed constituted 'the old days.' I refrain from referring to them as the 'good' old days. Those shifts were longer, the pay poorer, and the buses a darned sight colder, but people seemed to have been happier. Inspector Johnson left us all in no doubt that this was an honourable and skilful job, and if done correctly, could be justifiably considered a career for those who wanted to make it so. Contrary to what today's bus companies would have you believe - they say they can't afford to give training like that anymore! And so they don't. And it's my belief that the same can be said pretty much of the rail industry too. It was, in a way, like joining the army. This impression was emphasised even more on all of us when we were taken later the same day, and after the usual formalities of filling in varying forms for this and that, down to the basement stores. Here, we were each kitted out with our uniforms, including the little chrome, lapel numerals that designated our 'conductor number.' These were similar to the old police force 'dog-collar numerals,' and by these numbers, we would all henceforth be known. And of course, the part of any uniform that adds the final touch and denotes servitude in the wearer and officialdom to Joe Public - the peaked cap.  The uniform as a whole consisted of black trousers and

tunic, with silver 'Staybright' buttons, and the black polished-peaked

cap on which was the full crest of the city in silver Staybright with

its red shield. All this was to be worn with a white collar and shirt

and a suitably dark tie. The black tunic, with its two breast pockets,

reinforced the military look about it. At a distance, it would be easy

to mistake a tall, well-built, bus conductor - minus his cash bag and

ticket machine - for a policeman wearing a peaked cap. The uniform as a whole consisted of black trousers and

tunic, with silver 'Staybright' buttons, and the black polished-peaked

cap on which was the full crest of the city in silver Staybright with

its red shield. All this was to be worn with a white collar and shirt

and a suitably dark tie. The black tunic, with its two breast pockets,

reinforced the military look about it. At a distance, it would be easy

to mistake a tall, well-built, bus conductor - minus his cash bag and