|

MNBDOs & JACK'S JOURNEY being the journey of one Royal Marine 1940 - 1945 GIBRALTAR CAMP - LYNESS - DURBAN - SUEZ MEF CEYLON - SCYTHIA - ALGIERS - EXTON - DALDITCH - STONEHOUSE explaining RMFU, RMAB, MNBDO I & II, HBL 35 BGH, "FORCE OVERT" and other mysteries One man's story told through his memories and by interpreting his service record using existing free online resources. Jack's journey took him through Gibraltar Camp, Lyness, Durban, Suez, Ceylon, Exton, Dalditch and Stonehouse. In addition, the mysteries of some military abbreviations are unravelled. Without going into this deeper personal story below of just one Marine, it may be advisable to read this first ... click the link. MNDBO - an explanation of the Whys and Wherefores and some reasons why this information is so damnably hard to find. A link is provided on that page to bring you back here if you want to.

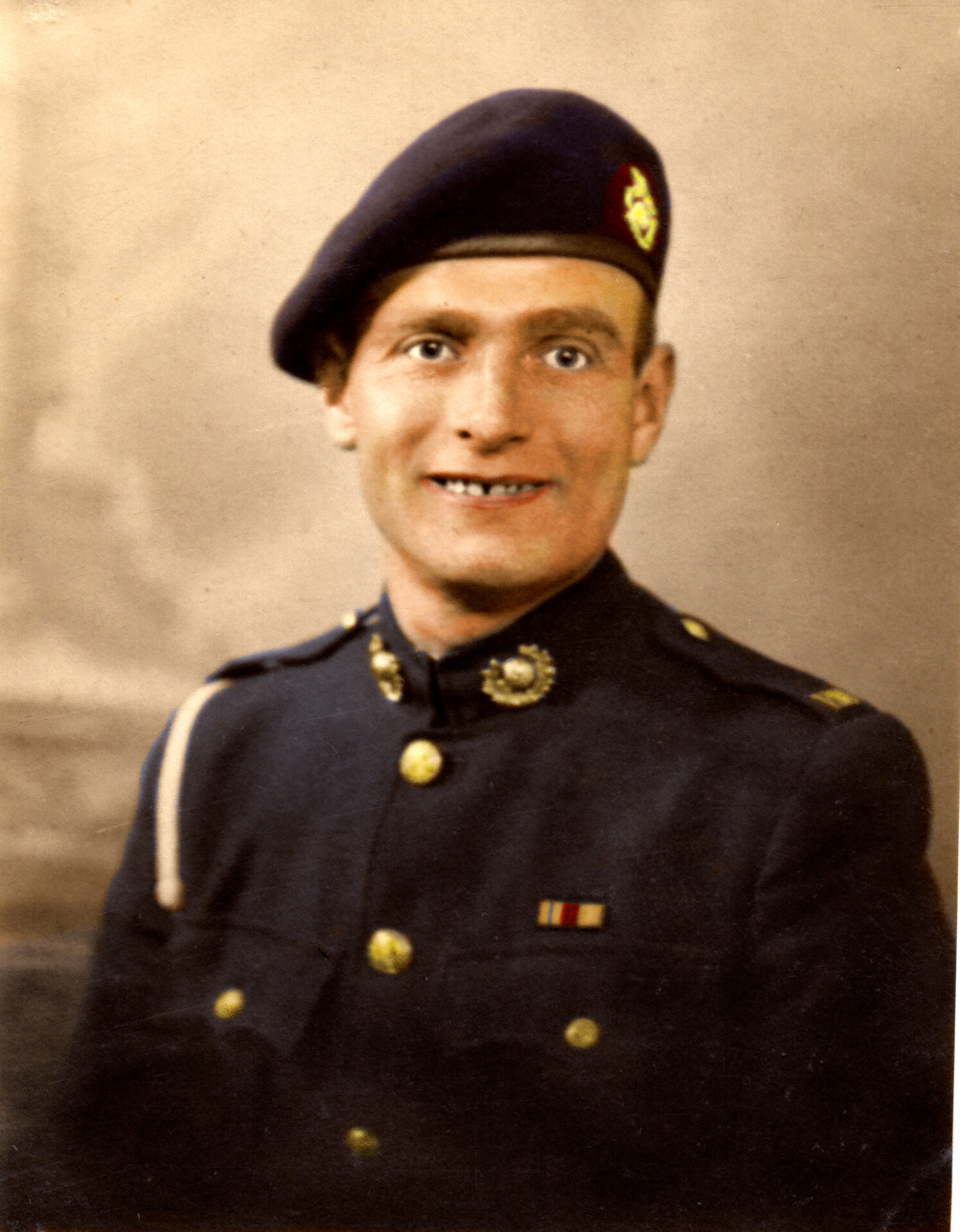

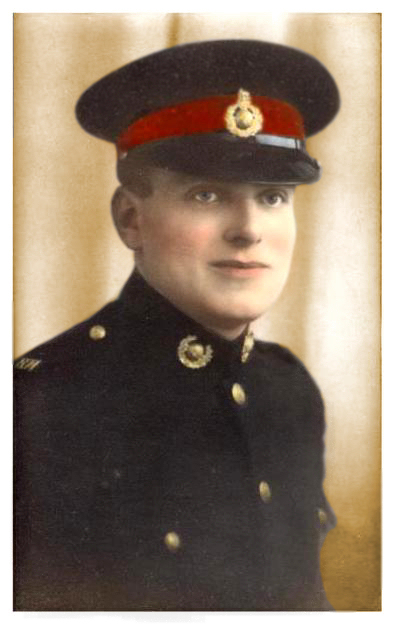

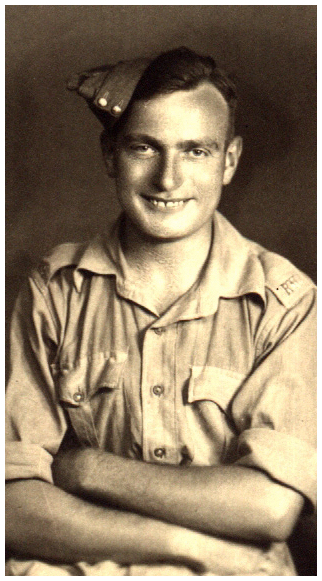

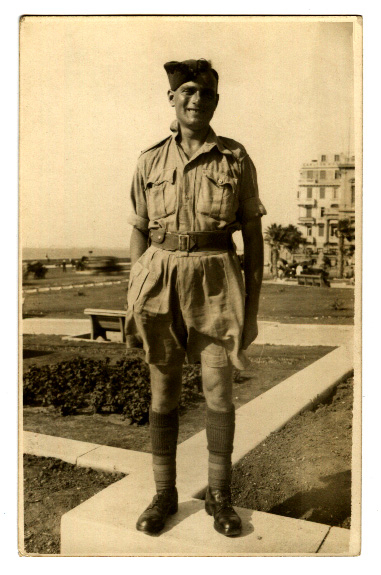

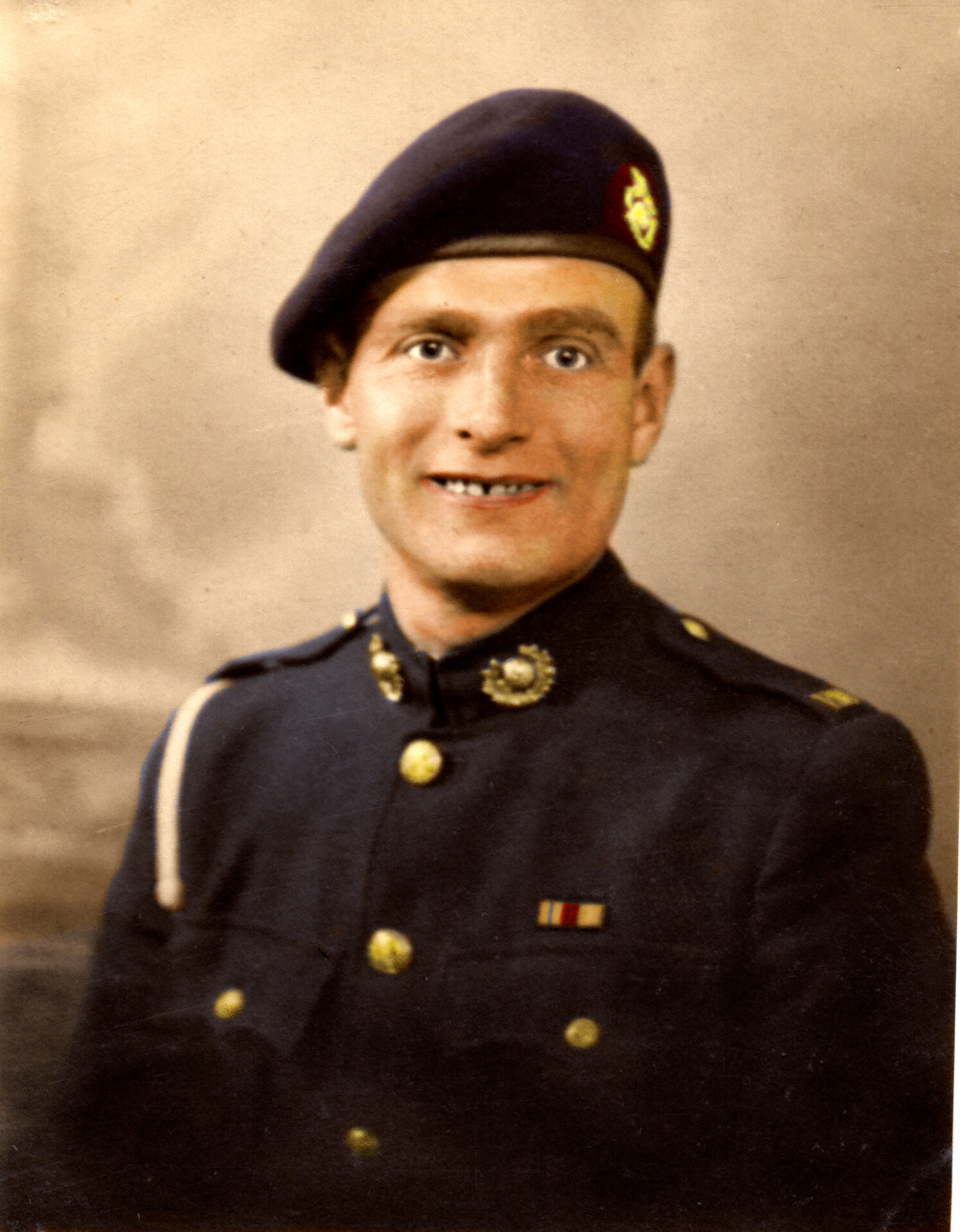

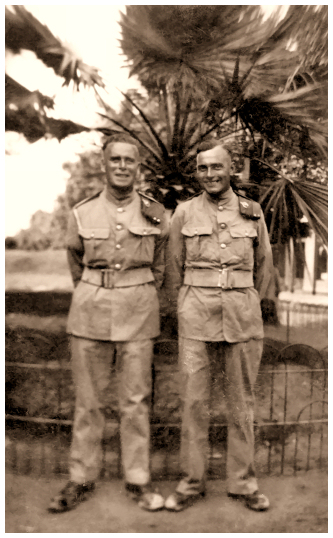

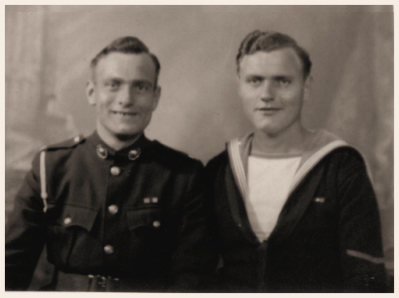

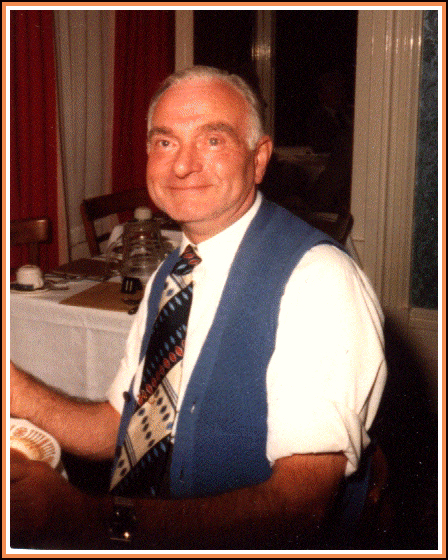

JACK'S JOURNEY For some years, I have researched the wartime story of my father-in-law, Marine Jack Stevens. The more I looked into it, and remembering much of what he told me before he died in 1989, I can only conclude that his story was not the usual story of Royal Marines serving throughout much of the war. To begin with, I must say that, although he didn't plan it that way, he never fired a shot, at least not in anger at any enemy. By his own admittance, he thoroughly enjoyed it, the whole experience. Talking in retrospect 30 years after the events, I sensed that he knew his memories of enjoyment were simply because he'd never had to do, or experience, what most of his mates did. To say he was grateful, I have no doubts about that. There were many times it could have all gone wrong for him, and by my reckoning, he had several lucky escapes. He revelled in the friends he made and the places he went, and he told me a great deal about it all. After he died, I wrote down as much as he told me, or as much as I could remember, which isn't quite the same but all family historians will know what I mean. Some time later, his widow gave us a 'memories tin', comprising mostly of rail and cinema/theatre tickets that Jack had kept as souvenirs of his travels. What is told here is the sum of what he told me, evidences from his souvenirs and photos, his recently acquired service record, plus further free research on the Internet. I hope that some of the information here, a lot of which would have been common to many Royal Marines serving at that time, may be of use to others researching the war records of their fathers, grandfathers and uncles in the same service. There were also quite a few photos, most of which we had seen whilst he was alive, and so we knew some of the stories behind them. It was a good while later that, mainly from those loose tickets and receipt stubs many of which were fortunately date stamped, we were able to put together a rough itinerary of where he went, and where he might have been on certain dates. In short, we were able to make a rough track of his progress through the war. Many years later and after Jack had died, using the Internet, I was able to flesh out a little more of the detail, with the help of RM veterans sites, Convoy Web, and my own limited knowledge of what was going on when and where in the war, particularly with regard to naval matters. As the years rolled on, more and more information on RM activities came to light as veterans told their own stories on blogs and forums where relatives posted up their own knowledge of what their dad or uncle had done during the war. One thing that slowly became clear was the apparent lack of information, particularly in regard to MNBDOs, exactly what they were, what they did, and where they went. That has improved somewhat in the last five years, and a full explanation of those initials appears later. I hope that this account of one man's service in an MNBDO will go some way to help other relatives puzzling over the same mystery. [Quick NOTE: added Summer 2018] But there is one thing you should know right away. If your man's record shows 'HBL', it stands for 'Home Based Ledger'. That is not what it looks like, far from it. I've recently seen a web blog where a relative was asking experts what HBL meant, and was told that answer, which is correct. So the enquirer asked if that meant that the man was always based at home, and was told that was true too. My word .. it's as far from the truth you can get. HBL was assigned to any man who was with a specialist unit; in other words, not assigned to a ship or fixed shore station. As you will see, MNBDOs were specialist units, of which there were two ... and both served exensively abroad, notably in Egypt, Crete and later Ceylon. If you have HBL on your record, along with MNBDO, your man most certainly left these shores, and for some time too. In both cases, he at least travelled in convoy around The Cape. There's more on this below; Please read on. Most relatives searching for information on an MNBDO will quickly be guided to the Royal Marines Museum website, or one of the many blogs where they quote verbatim from that site all that was officially known then about both of those units. What was lacking was any real detail of exactly where they went and when, and that is still true today to a large extent. It's not the fault of the RM records office, or anyone else's. The lack of information comes about simply because it was all so blesséd complicated, something which I hope Jack's story will in some measure clarify for others. It is my belief there is much more detail out there of where MNBDOs were sent, but it's still all tied up with individual families, in their memories of what dad or grandad told them, and in 'memory tins' and photo collections such as Jack's. I am sure the historians at the RM museum suspect this too. Over the years, their visitors will have dropped many snippets of information, much of which may have seemed unimportant at the time, but it all builds up to a more complete whole, at least a better picture than that given by the RM official histories. But for the time being, we had to leave things as they were, and hope that one day, we'd get around to sending for Jack's service record. I don't know what took us so long. SENDING FOR HIS RECORDS More recently, in 2015, we finally got around to fulfilling that promise, and sent for Jack's service record from the RN&RM records office at Whale Island. Royal Navy veterans will remember it as the RN gunnery school, HMS Excellent, which was also a very strict and severe Physical Training Centre, as well as a naval prison for 'serious defaulters'. It's now also the home of the RM Band Service, as well as first port of call to send for a man's records. Surprisingly, Jack's records came back fairly quickly, within a fortnight of sending off the forms and the £30 cheque. I say this in comparison to army records, which we heard from friends can take far longer, as much as six months on occasion. Having sat back and prepared to wait, when they plopped on the mat they took us rather by surprise. At last, as we opened them, we knew we were now finally going to fill in the gaps of where he went and what he did, and more importantly, which units he was part of and where they went. We would now be able to trace his movements around the Middle East and over to Ceylon. Huh. Wrong! By and large, we didn't learn a great deal more from his records, geographically, than the few details we already knew. There were a number of forms, lots of detail to go through, and at first glance, details of drafts and various units. Taken by surprise, we looked again, then went through them again. And the one place we became flummoxed on was the initials 'MNBDO.' Because of my previous research, I did already happen to know what those initials stood for, and what they did. But there was no mention whatsoever of foreign climes, troopships, or ocean travel of any sort. That still left us with a mystery, as I suspect looking at forums and blogs everywhere, that baffles most researchers. That is the main reason for posting this very long page, so I hope it helps you too. MNBDO ... what is it, and what does it do? It stands for 'Mobile Naval Base Defence Organisation'. A rather enigmatic title, and whether that caused confusion in any potential enemy spy, we know not. But it certainly confused us! It was rather a mouthful, and I wonder if it ever occurred to the chiefs in the corridors of Whitehall and the Admiralty that years later, some former members would be hard pressed to actually remember its name, let alone what they did. It's much easier to remember the name of a ship. A man could remember several ships after 40 years, rather than those vague initials. British officialdom has always relished and enjoyed inventing new acronyms of the mysterious kind. The forces were already full of similar obscure titles, and I suppose yet another didn't particularly jar with anyone for them to find it odd. As to its meaning, we soon learned that it certainly did what it said on the tin, to use modern parlance. They certainly were mobile, and devised to defend naval bases. The word 'Organisation' is an odd choice, but that is what they were. The term 'Group' may have been a better choice, for in effect within the corps, they were known as Group 1 or Group 2, MNBDO. I've no doubt that marines at the time, drafted to a MNBDO, looked at their draft chit, frowned deeply and said, "Who?". Turning to an old hand, a long-service marine or NCO, one might have got the answer, "Oh, that's just the fancy new name for a Fortress Unit, don't worry yourself about it." I wish I had asked Jack what he had thought about it at the time, but I'm sure he would have brushed it off with the line that they didn't ask questions and just obeyed orders. I've also no doubt that most invented some humorous and pithy other meaning - probably not always polite! Let's clear up some of the various ways these initials are displayed in blogs, forums, generally around the Internet. It surprises even me, to find such a wide variety. It did NOT stand for, as some ex-Bootnecks would have it, "Men Not to Be Drafted Overseas." If in an MNBDO, a man almost certainly was posted overseas, despite what it might first look like on their service record.