THE EULOGY

Read out by the minister at Mavis' funeral, when

she died in March of 2017, just short of her 94th

birthday. Her long life was not matched with good

fortune, but beset with tragedy, and this is her

story.

THIS IS MAVIS' STORY

Mavis Wardle was a wife, a mum, a grandmother and

a very treasured aunt.

This lovely lady you all knew, by one of those

titles. We pay tribute to her now, and as we give

thanks for the almost 94 years of her life, I

think we also give thanks for the privilege of

just knowing her. For we have all benefited at

some time in our lives from her kindness, love and

generosity. It is hard to recall now how hard her

life has truly been, for although Mavis did find a

great deal of happiness and contentment in family

life, she would also know more than anyone's fair

share of tragedy. Brought up in a Methodist chapel

family, she had a reassuring belief and faith that

would sustain her during her darkest hours.

And there were many of those.

Mavis was born on May 1st, a Mayday baby, in 1923.

The third of four daughters, to Harry and Violetta

Holt of Coalville, the four Holt girls were

affectionately known by their father as his "four

GEMS", from their initials - her sisters being

Gladys, Edna, then Mavis herself, and the youngest

Sylvia. Little jewels they were too. The Holt

family were well-known in Highfield Street, and

their early years were marked by regular

attendance at chapel and Sunday School.

In the dark days of the middle of the Second World

War, aged 19, Mavis met and married naval rating,

Jack Hill, in the late winter of 1942, and this

just a year or so after the four daughters had

lost their mum to cancer. Harry, a veteran of the

First World War and now a widower, had struggled

tirelessly along with Violetta bringing up his

four girls during those endless hard years of the

20s and 30s.

But tragedy was to strike the family again, within

weeks of Mavis' marriage. Her new husband would be

lost at sea in mid-Atlantic when his ship was

torpedoed and sunk. Mavis would receive the

dreaded telegram to learn that Jack was posted

missing, and then, only weeks later, would

discover that she was expecting Jack's son. Now a

widow, with a child on the way, life must have

seemed more than harsh. The war's end, and victory

when it came - as it would have been for all war

widows - must surely have been so bitter-sweet.

It was in the years from the mid-forties to

the mid-fifties that Mavis became particularly

close to sister Edna. With older sister Gladys

married and without children, and younger sister

Sylvia still a young girl, it was natural that she

would be drawn towards Edna, and her two sons,

Alan and Rodney, who were to become natural pals

and playmates to cousin Michael.

They became inseperable during these years, and

Alan remembers some of the times spent together:-

walking to Bardon Hill for a picnic, so that the

three boys could scramble around together. Or on

many occasions catching the bus from Coalville to

Whitwick, and walking up to Spring Hill, and

sitting on the hillside amongst the bilberry

bushes picking bilberrys for pie and jam making.

The three cousins were supposed to be helping with

the picking but tended to consume more than they

contributed - ending up with purple fingers and

lips. Then it was down to Spring Hill Farm for a

bottle of Vimto and perhaps an ice-cream whilst

Mavis and Edna would have a cup of tea.

Whilst all three sisters were very close to Mavis,

it was Edna that spent the most time with her

because of the boys naturally wanting to be

together.

So apart from the welcome help within the family,

Mavis spent several years alone, bringing up

Michael, but always hoping against hope that Jack

may well turn up one day - he was after all, just

'missing', as he was never found, and it was not

unknown for such things to happen. But slowly,

acceptance took hold. When Michael was still a

little boy, in the early 1950s after some ten

years of widowhood, Mavis did again find happiness

when she met Percy Wardle, our beloved grandad and

uncle of memory, and they had many happy years

together. In Percy, Michael found the loving

father that war and fate had robbed him of. But

Jack was never forgotten, and frequently talked of

in the family, all the cousins being always aware

of the sacrifice Michael's father had made, as

well as of Mavis' loss.

Percy worked, for a short time, on the Midland Red

as a conductor. At that time, Mavis and sister

Edna worked at Chad's café on Coalville Clock

Tower, a favourite tea stop beloved of Coalville

bus crews. So both sisters were destined to meet

their husbands there. Mavis and Percy eventually

settled in Newbold Verdon, which would be Mavis'

home village for the next 50 or more years, and

they went on to have a son of their own, Phillip.

Sadly, years later, when working at Desford Tubes,

Percy was to suffer a terrible accident at work

which so badly injured a foot that it did in

effect cut short his life, and he died in the

mid-1970s leaving Mavis a widow once more, and for

this past 40 years or so.

It is hard to credit how tragedy can strike one

wife and mother so many times, but in the years

that followed, Mavis would also lose both of her

sons; both at a similar age in their forties, and

both through heart disease. The death of first

Michael, and then 15 years later, Phillip, added

to her ever increasing burden of loss.

Michael's widow, Val, was a great comfort and

constant companion for many years after, on many

frequent and enjoyable shopping trips and days

out.

Nonetheless, Mavis meeting with her friends in the

village, usually at the weekly Monday Lunch Club,

and throughout retained a faith that is a lesson

to us all, displaying a quiet strength, love and

fortitude that we can only marvel at now, given

all that befell her.

In those later times, Mavis' found great

consolation in the company and love of her

grandchildren. Anna-Marie, John and Ross were a

great joy to her over the years, as were her

several nephews - as well as continued contact and

regular meeting with her three sisters, all of

which would themselves die long before her. Mavis

always said she didn't want to be 'the last one

left,' but time and events would prove it to be

so.

Later years would see the increased infirmity that

led to her reluctantly giving up the Newbold home

she had shared with Percy and her two boys, to

move into the bungalow at Barwell. By this time,

grandson John, along with Clare, now very much

taking on the mantle of his late father, made it

their job to care for their grandma's best

interests and to be sure she had all she needed in

her new home. It must have seemed that she was

leaving some very deep roots, and then again, even

more so to move yet further into Barwell where she

found sanctuary and friends in Saffron House

retirement home for her more peaceful last years.

So today, we not only remember Mavis, and thank

providence that she was our grandmother and aunty,

we remember all those that she so dearly loved,

all those that have gone before, in war and peace,

by accident and ill-health or, like Mavis herself,

through that toll which age and time exerts on

each and every one of us.

Mavis, that lady so quietly spoken, so

kind-hearted, the last of her generation, who

showed us that tragedy and adversity really could

make us stronger, but above all else, showed us

all, such unconditional love and affection.

We give thanks that we knew, and loved you. We

miss you.

THIS IS JACK'S STORY

Many boys of the 1950s generation grew up knowing

of brothers and cousins, fathers and uncles, that

didn't come back from the war. Many a lad was

influenced by the stories attached to those family

tragedies. So it was for me.

I heard all about how Uncle Jack was a gunner, who

had died at sea, was reported missing, serving in

the Royal Navy. There were a few unusual facts in

the story that perhaps even my mother didn't quite

understand herself, and she would have been

astonished at what we have found out since. But

for me as a 10-year-old lad, they were over my

head and only became something of a mystery in

later years. Suffice to say that Jack, though long

dead, instilled in me a life-long interest in the

Royal Navy, enough for me to start reading stories

of naval history at quite a young age.

Aged about 10, the real interest sparked when I

picked up a tattered copy of a paperback book at a

Scout bazaar - costing about 6d if I recall

rightly and a week's pocket money - about the

famous 'Battle of the River Plate'. This sea

battle had been the first significent naval action

of the war, one that had literally occurred only

twenty years before I was actually reading about

it. Memories of those dark days for folks older

than me were still very fresh, raw even, and all

very much still in the recent past. I learnt of

how our naval gunners had beaten off a much larger

German warship and ultimately won the day. That

famous action would prove to be our only real

victory for quite some considerable time.

I often wondered if the stories of that battle, as

they had filtered down through news just before

that first Christmas of the war, had also

influenced the 18-year-old Jack in some similar

way. The fact that I never succeeded in joining

the navy myself was not for want of trying, but

that is by the by. But that deep interest did help

greatly, over 50 years later, to uncover some

remarkable facts about Jack's service, if only in

having some inkling as to where I might find them.

Jack was lost at sea just eight years before I

came into this world. Still very much a presence

in the family, the grief still deeply felt, I

recall my mum telling myself and my brothers in

the 1950s the story of how her sister, our Aunt

Mavis, had met and married a sailor. How within

six months of their marriage, she had lost him to

a German U-boat. Of how she had waited years for

his return, for she never gave him up as dead.

Somehow, Mavis always believed, always felt, that

Jack had actually survived the sinking of his ship

and one day would return.

So Jack was really my uncle by marriage and

therefore my mum's brother-in-law. In many ways,

because of Jack's influence on all of the Holt

family, the Holt family story is paradoxically

also Jack's story. One paradox was that his real

name was not Jack. He was christened John William

Hill when he was born in Donington le Heath in

1921, and like a lot of boys called John, he

assumed this obvious nickname as a lad, and kept

it. I do also wonder if 'Jack' being the

traditional affectionate name for a naval rating

had some bearing on Jack himself joining the navy.

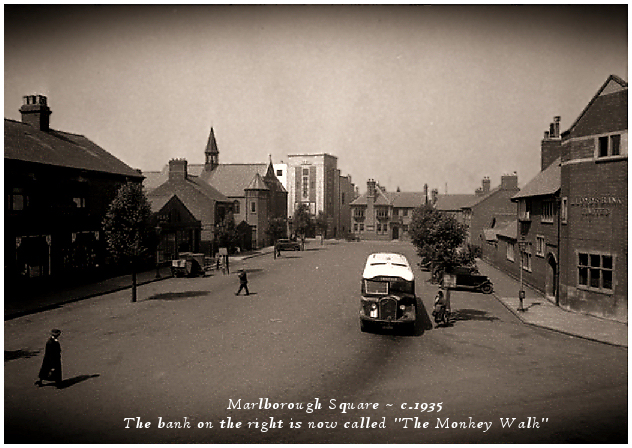

Mavis was 19, and her younger sister just 12, when

she met this dashing young naval rating on “The

Monkey Walk” in Coalville. Along the north side of

Marlborough Square there was, and still is, a wide

footpath that was colloquially known by that

somewhat disparaging term. This tongue-in-cheek

name has become so much embedded in local folklore

that a pub, on the site of a former bank, is known

by exactly that name today. It appears the

tradition lives on.

It had long been the practice, almost from when

Coalville as a town was first founded, for local

lads and lasses to 'promenade' in that area on

fine weekend evenings as a way of finding boy and

girlfriends, and perhaps ultimately a marriage

partner. Dances and cinema trips would then be the

usual routine as couples got to know each other

better, or not, as the case may be.

So it was exactly in that way that Mavis met Jack.

Mavis, and her three sisters, had not long lost

their mum, the year before in 1941. Violetta Holt

had succumbed to cancer aged only 41, in the

second full year of the war, leaving husband Harry

a widower and four daughters bereft of their mum.

Harry was a miner, a veteran of the Great War,

whose own wartime experiences had left him with

ongoing issues of depression and nervous anxiety.

It was a common problem for tens of thousands of

men coming back from that monumental conflict, and

one that we would today almost certainly call

post-traumatic stress disorder. Harry had a couple

of periods of 'convalesance' in the 1920s and

1930s, periods of quiet away from the family to

recover from nervous exhaustion. Life for any

miner in the Coalville in that era was an ongoing

financial struggle to make ends meet.

Nonetheless, Harry and Violetta had brought up

four daughters, Gladys, Edna, Mavis and Sylvia,

affectionately termed by their father as his four

'GEMS', after their initials. The family were

well-known in Highfield Street, and their weekly

routine was governed by their father's shifts at

South Leicester Colliery, the girls' schooling at

the village school in Hugglescote, and chapel.

Attendance at chapel was required twice on Sunday,

once to Sunday School for bible instruction, as

well as either the morning or evening service.

Harry and Violetta were strong Methodists, as were

many folk in the area. Violetta's own father was a

lay preacher in Shepshed, and the christian faith

ran very deep on both sides of the whole family.

In 1941, at the time of their mother's death, the

youngest girl, my mum Sylvia, was then 11. The

loss of their mum hit all of the girls very hard,

as can be well imagined. The eldest at 26 years

was Gladys, by then grown and already left home to

work in service to a Loughborough family in the

bakery business.

The next eldest sister, Edna at 23, was already

married with a young son. Then came Mavis, 18, and

lastly Sylvia, her baby sister. Mavis had been 7

when Sylvia was born. They were a typical miner's

family, in a town and street of similar mining

families.

If not employed at mining or other work at the

pit, most local men were 'on the railway' or on

the post, on the buses, or worked for the local

council. The rest were in various light and heavy

engineering or electrical workshops and trades,

many of which were connected to or supported the

mining industry. And a great many of the men over

the age of 45 were war veterans, just like Harry.

That early naval victory mentioned above was a

rare victory indeed, for there were no more to be

had for a very long time indeed. Once the war

really got going, in the spring of the following

year in 1940, it was a seemingly never-ending

story of defeat and disaster, withdrawal and

retreat. Things just went from bad to worse, the

only slight relief perhaps being the Battle of

Britain, which at the time was not even regarded

as the great victory it is today, but merely as a

relief from the immediate threat of invasion and a

certain and comprehensive defeat. By 1941, when

Mavis' mother took seriously ill and cancer was

diagnosed, her passing in late summer was

relatively swift by today's standards. Certainly,

by the Christmas of that disastrous year, things

were very bleak indeed, and not just for the

Holts.

It might have been true that immediate invasion

had been staved off, but the war news just went

from bad to worse, all down the line. Shipping

losses at sea mounted, defeats in North Africa and

the Mediterranean came one after another. For a

generation like Harry's, who thought they'd fought

'the war to end all wars', the world must have

seemed to be coming to an end. Indeed, for Harry

and his four daughters, it already had.

Thousands of British and Empire servicemen and

women had already lost their lives to the German

onslaught, and on top of that, the war was also

now being fought at home. Bombing of cities and

towns had started soon after the Battle of Britian

had ended, and from then on they just increased in

number and intensity. Sylvia herself recalled

standing with her mum and sister at the bottom of

their father's garden, looking over the fields of

Standard Hill and seeing the glow in the southern

sky as the centre of Coventry burned to the ground

some thirty miles away.

Coalville itself, small town though it was, was

not immune to air raids, with some nearby

factories already targets of the Luftwaffe by

reason of their manufacture of all sorts of

materials for the military. For the Holts, as bad

as the First War had been, notably in the

unprecedented number of men's lives lost, this war

now seemed far, far, worse. And late in 1941,

there seemed to be no end to it all. Victory, even

if it could be achieved, was a long, long, way

off, at the end of the darkest of tunnels, down

which there was no visible light. The sheer

disappointment amongst the older generation that,

despite all those sacrifices of the First War, and

all those promises made thereafter, that it had

all been for nothing, must have been very

palpable.

From a naval point of view, late May of 1941, saw

the worst naval disaster so far during the episode

of the sinking of the 'Bismarck'. But even that

victory had been at a very great cost, of more

than 1,400 men killed in the unbelievably tragic

loss of the pride of our fleet, “HMS Hood”.

Other European countries were going down before

the German jackboot like flies, Crete had been

lost with enormous casualties, and then in the

summer, the apparently unstoppable German war

machine had invaded Russia. Surely, things could

not get any worse.

But they did. The attack on Pearl Harbour, closely

followed by the naval disaster of the loss of

another two of our best and biggest battleships,

along with most of their crews with nearly another

1,000 men lost and as many again taken into

captivity, all must have surely sent a shiver down

the spines of even the most stout-hearted. Now

there was war with Japan too; folks must have

asked, how on earth were we going to even manage

that, let alone win it. The only bright spot was

that the Americans were now involved and we were

not alone any more. It was their involvement that,

in the most curious of ways, brings us back to

Jack's story.

Exactly when Jack joined the Royal Navy, on which

date, we don't know. Whether he volunteered and

chose his service, or was conscripted and assigned

his naval role, we don't know that either. He may

even have joined right at the start of the war,

aged 18, and so perhaps had already been an old

hand and seen some service. If for some reason he

had deferrment from 'call-up', he might not have

received his papers until he was 20. My guess is

that the latest he could have joined would be

towards the end of 1941 for his basic training,

then having been selected for training as a

gunner, would have almost certainly gone to the

naval gunnery school on Whale Island, 'HMS Excellent,'

to learn his job. His wedding photo with Mavis, in

the late winter of 1942, shows him proudly in his

Number Ones, the term for a naval rating's very

'best blues'.

Whatever the answer to how he came to be in the

navy, he was proud enough of his job to make sure

the sleeve of his arm was pulled round just a

little bit to show off his shining new gold,

gunner's badge. The gun, with one star above, and

the letter 'Q' below, denotes that Jack was a

'Quarters gunner – 3rd class', so very junior and

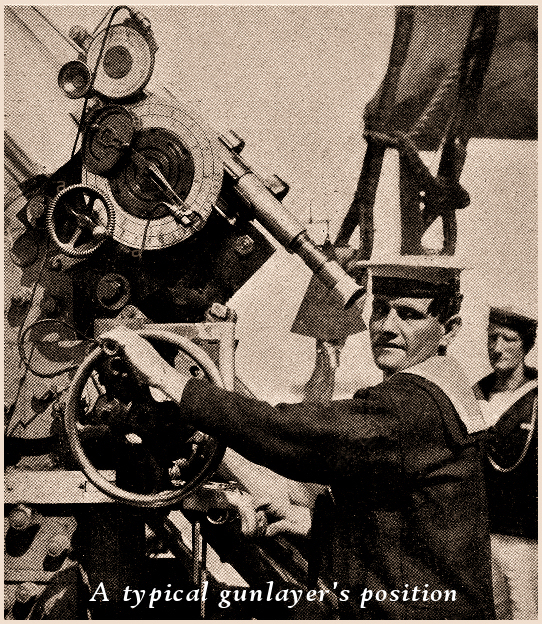

literally just out of training.

In effect he was a gun layer, and would sit in the

gun layer's seat, a bit like an old fashioned farm

tractor seat. He would raise or lower the angle of

the gun, and train it to the left or right for

firing, by quickly turning the adjustment wheels

whilst also looking through the long telescopic

lens at his target. Another rating loaded the gun

manually by lifting the shell and sliding it into

breech itself. Yet another would slam the breech

door shut and possibly press the button to fire

the gun when ordered by the gun captain.

Jack was one of a team of four or five men to each

gun, and his job was to ensure the gun was on

target, both for direction and elavation.

To understand more of what Jack did, what he

trained for, and the circumstances of his loss, we

need to delve a little into the background of

those aspects of the naval war at sea that would

ultimately determine his story.

Much of this is well known to the wartime

generation and those such as myself who came

shortly after, growing up steeped in the stories,

terminology and folklore of that huge conflict,

but as time passes, it is less well-known amongst

younger generations. Even lads of my post-war

generation knew the difference between a

battleship and a destroyer, or the effective

ranges of a 15-inch gun compared to a 4.5-inch,

from when they were at junior school. Perhaps some

filling in of basic information may be helpful

here, as well as placing events on a timeline that

puts things into context for Jack and Mavis and

their families.

By that Christmas of 1941, we were not only

building more warships of every size, but also

'borrowing' extra ones from America, those being

the 50 redundant, leaky, First War destroyers that

we gained on 'lend-lease'. All these, as well as

the ones we were frantically building for

ourselves, from aircraft carriers down to tiny

corvettes and minesweepers, had to have crews, and

all needed gunners. In fact, along with all the

other trades and skills, we needed lots of

gunners, and very quickly.

By the time Jack was doing his gunnery training,

German submarine attacks on our merchant shipping

were already taking their terrible toll. The main

answer to this type of attack was to organise

shipping into convoys, hopefully escorted by

enough warships to deter U-boat attack, and if not

deterred, then at least to attack the submarines

themselves.

The Admiralty's plan was simply to revert to what

had been done in the First War. Huge convoys with

armed escorts was the larger answer, but with

merchant ships also being given some form of

armament to defend themselves as best they could.

Shortage of warships of all types meant that some

convoys were not escorted at all. Defence also now

meant against air attack as well as submarine or

surface attack, and therein was a big problem for

the British government.

Just as in the First War, there was great

political unease about what to do about unarmed

merchant ships. This worry came about out of

British nervousness about not being seen to play

by the rules – the rules of war. Those rules are

governed by the Geneva Convention, a rulebook

still observed by most democratic countries of the

free world. Following the horrors, and some would

say unethical German practices of the First War,

such as sinking merchant ships without any prior

warning, previous conventions of warfare were

updated in 1929 at a huge world-wide convention

held in the Swiss city of Geneva. These strict

rules covered how non-combatants and civilians

would be treated, as well as the treatment of

prisoners-of-war. They covered how war could be

waged at sea, what actually defined a warship and

what didn't, and indeed, what was a civilian and

what wasn't.

The German argument, used to justify torpedoing

merchant ships without any warning in that First

War, deemed that any ship that carried arms or

munitions of any sort made it a warship, and

therefore liable for attack and to be sunk –

without warning! They applied this warped logic

even to passenger liners with women and children

aboard.

In the end, for our government and the admiralty,

it all came down to a name. Having decided that

merchant ships would now most certainly have to

have arms to defend themselves from all sorts of

attack, it was simply a matter of what they were

called, the terminology, but without being seen to

break the rules. Therefore, they were designated

'Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships.' Otherwise

known as 'DEMS'. It was a feeble effort to make

the point that they were, after all, just merchant

ships. Not that any amount of messing with words

bothered the Germans one bit, not in that war or

the First.

Merchant ships would be fitted with large calibre

naval guns for seaborne defence, and fixed or

mounted machine guns for air defence. Merchant

seamen, are and always were, civilians, and the

rules of war were that they should be treated as

such.

So although it was not at first deemed appropriate

for a ship's own crew to man these newly mounted

guns, on many ships, they did just that. It was

always intended that the job of maintaining and

firing the guns would have to be done by Royal

Navy personnel, but it wasn't always so, and not

always possible. In fact, on a few British

merchant ships, guns were manned by army personnel

of the Royal Artillery. But from the point of view

of the rules of war, if a merchant ship was

captured, the civilian crew should be treated as

civilians and ultimately returned to their home

country, and naval ratings were properly

prisoners-of-war and could be detained as such. It

was natural enough that the naval gunners destined

to man these guns would be called DEMS gunners,

which is how we know them today.

Naval ratings, also known by the slang term of

'matelots' (pron: matt-lows), as well as 'Jacks',

who passed their course at gunnery school would be

assigned their ship according to the size of guns

they trained on. A new gunnery rating couldn't

hope to be drafted to a huge battleship with the

biggest 15-inch guns; he would learn his trade on

smaller guns first.

The calibre of guns back then were designated in

inches, the number being the diameter of the

opening in the gun barrel across the centre from

one side to the other. The guns fitted to merchant

ships tended to be the old secondary armament from

redundant cruisers or destroyers, so were most

likely to be 3-inch or 5-inch naval guns. A 3-inch

gun, although regarded as small and something of a

pea-shooter in big gunnery terms, could still

punch a fair sized hole in the hull of a submarine

wallowing on the surface. Two hits would almost

certainly be fatal. Armed merchant ships, given

the chance of a fair fight, could give a very good

account of themselves.

It was on guns of such size that Jack would find

himself working. The circle of a 5-inch shell

placed standing up on its end would cover roughly

half the width of an A4 sheet of paper, and

perhaps be a little more than the length of a

computer keyboard in length. They were heavy,

though not too heavy for one man to carry.

Generally, they were loaded into the breech of the

gun by hand. Fate would determine that Jack would

volunteer to be a DEMS gunner, and so be posted to

a merchant ship - but as a Royal Navy rating.

Though this particular posting would be slightly

more unusual.

When the USA came into the war during that fateful

December of 1941, one thing quickly became very

apparent for their navy. They didn't have enough

gunners either, not even enough to man all their

own warships. They certainly didn't have enough to

man their massive fleet of US merchant vessels as

well. So an agreement was quickly reached with the

British government; we would 'loan' them some of

our naval gunners to cover their shortfall until

enough of their own naval ratings could be trained

up.

Unlike Britain, the Americans never had any qualms

over terminology or the need to use long, vague

acronyms to describe a gunner. Not for them the

worry of issues over whether defending a grain

carrier or oil tanker was an act of war or not,

nor the use of the word 'arms' or 'armed'. They

came out with it plain and simple; their naval

gunners on merchant ships were designated 'Armed

Guards'. Their ratings were in the United States

Navy and wore the badge 'AG' on their uniform

sleeves.

Jack would incredibly find himself one of a very

small number of RN men to be loaned to the

American navy, to work alongside their Armed

Guards to make their numbers up. I say

'incredible' because, he would not have expected

such a turn of events, and would have scarcely

believed it when first told where he was going. On

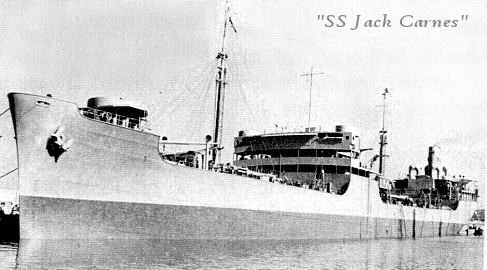

Jack's ship, a large oil tanker, the requirement

needed to man all the guns was for fourteen men.

This was made up of twelve armed guards, and two

Royal Navy DEMS gunners.

Thus Jack, having volunteered for 'DEMS' service

and undergone further training, would receive a

'draft chit' telling him he would be a gunner on

an American tanker, the 'SS Jack Carnes'. This

tanker moreover was brand-new, one of dozens being

built at the same time as the American war machine

revved up to maximum output, having only been

launched the year before and had just made it's

maiden voyage only in the February, 1942. Another

fact we cannot know is just where Jack joined his

namesake ship, but we have to presume it was from

a UK port.

A great deal of information we have now is by way

of the internet, and the massive host of websites

of the last 20-years or so that deal with wartime

naval matters, from lists of ships sunk, to crew

lists and naval veteran memories. There is a great

deal of detail out there now, much of which Jack's

family, and namely Mavis, when they first learnt

of his loss, could never have been aware of. All

they knew was what the Admiralty telegram told

them at the time, and perhaps a little more detail

later when it was revealed that Jack was in fact

serving on an American tanker, and they learnt of

its name and approximate place of its loss.

Indeed, as a lad learning about Jack first hand

from those that knew him, that is all I would know

too for the next fifty-something years.

One of the snippets of information we gain now is

that this new coal-fired steam tanker, owned by

the Sinclair Oil Company and built at Wilmington

on the Delaware River, was a very busy ship

indeed. Other information from another website is

that this new tanker did a run to Murmansk on the

perilous arctic convoys. But I am satisfied now

that this was a story put about by the relatives

of one of the American crew's survivors, perhaps

from misunderstood information, extracts of which

still appear online, but it is mistaken. Firstly,

the ship's name does not appear on any of the

arctic convoy lists available online, on any of

the outward or return runs to Russia.

Secondly, the ship's name does appear on the

excellent 'Arnold Hague Database' online, as part

of the website, ConvoyWeb. Therein is the 'SS Jack

Carnes' story, a full list of ports, arrival and

departure dates, from when she set out on her

maiden voyage on February 25th from New York. All

possible dates are accounted for even allowing for

minor errors. She spent the first few months of

her career between the oilfields of The Gulf of

Mexico and New York, then made one trip through

the Panama Canal and round to Brisbane, which now

turns out to have then been a little suburb of San

Francisco, with an oil terminal. The data records

her passing through the ports of Cristobal and

Balboa on the canal in both directions, thence

back to the Gulf to collect a cargo of oil for her

first trans-Atlantic trip, to Belfast.

But we can be confident that she made those

voyages without Jack. The earliest Jack could have

joined her would have been July 21st, when she

left Swansea for her first trip back across the

Atlantic, this time to Aruba, to collect another

cargo of much needed oil. She seems to have

brought oil from Texas City in the Gulf to Belfast

the first time in late June, then called at

Swansea to rebunker, before her first trip back

across the Atlantic to Aruba. She came back to

Belfast once more with that cargo, then once more

to Swansea to rebunker again. If he joined on 21st

July, that would fit with embarkation leave

following completion of his DEMS training, which

seems to have nicely coincided with his 21st

birthday at the end of June. In which case, Jack

had already been to Aruba once, and was on his way

back to that port again when he was lost.

After Jack and Mavis had married in Coalville, in

the spring of 1942, Jack would have had a very

short leave, possibly when straight out of his

first gunnery training, but prior to his further

DEMS training. It is also very likely that on the

day of his marriage, he had no idea where or to

what ship he would be going, or even that he would

become a DEMS gunner, though he may have already

volunteered for the role. The badge on his sleeve

does not denote that distinction, so it is also

likely that he went straight off to DEMS training

right after his wedding. It would then be after

that further training period that he would have

had one more period of leave, maybe a couple of

weeks or so, on what might be termed 'embarkation

leave'. This was routinely given to service

personnel about to serve a period of time abroad

and for whom 'Home Leave' would not be an option

for a couple of years or more.

The badge Jack would have

worn after his DEMS training

To the best of our knowledge, this leave would be

the last time Jack and Mavis would see each other,

sometime during June of 1942. Jack had his 21st

birthday towards the end of June, on the 26th, and

all forces personnel, if still in the UK, used to

move heaven and earth to get home for that special

day. It is not unreasonable to suppose Jack was

home with Mavis for that day, and maybe for a week

or so after. The coincidence of training courses,

imminent and indefinite sea service and his 21st

would have been just too much a temptation to not

to try and do something to get leave to go home.

To the best of our knowledge, this leave would be

the last time Jack and Mavis would see each other,

sometime during June of 1942. Jack had his 21st

birthday towards the end of June, on the 26th, and

all forces personnel, if still in the UK, used to

move heaven and earth to get home for that special

day. It is not unreasonable to suppose Jack was

home with Mavis for that day, and maybe for a week

or so after. The coincidence of training courses,

imminent and indefinite sea service and his 21st

would have been just too much a temptation to not

to try and do something to get leave to go home.

When an oil tanker discharged a cargo of oil, it

was the practice to then re-load with thousands of

barrels of fresh water ballast. This prevented her

from riding too high in the water as an empty

vessel, for a rudder and propeller half out of the

water makes a very inefficient ship. Having

unloaded oil at Belfast Lough, she then loaded the

water ballast, and crossed the Irish Sea to make

her way to Swansea docks to rebunker with Welsh

coal. From there, she crossed the Atlantic to

Aruba, in the southern Carribean, in order to load

yet another cargo of much needed oil for Britain's

war effort.

The dates on the database quoted above tell us

that the 'Jack Carnes' had already made one trip

to Aruba, then back to Belfast, and then Swansea.

She arrived in Swansea again to rebunker with coal

on August 22nd, and sailed for Aruba on the 25th.

That is the very latest Jack could have joined his

namesake ship. The only certainty is that when the

'Jack Carnes' departed Wales once more, Jack was

aboard for that second run and about to fulfill

the role he had trained for. But, given the dates

we have, and surmising when Jack had leave and

when he would have finished training, give or take

a week or so, it is very possible he was on that

first run to Aruba too. In which case, he had

already crossed the Atlantic once, and was about

to do so again. Only his full service record will

tell us when he actually became one of the 'SS

Jack Carnes' ship's company, and indeed, when he

actually joined the navy.

Another snippet of information that comes out of

the research is that all DEMS gunners were

volunteers for that role. He must have asked, or

been suggested, for the role and then agreed to

the job, and as such, would then have been

appraised of the 'risks'. All volunteers would

have been told how dangerous it would be, in more

ways than one, and not just the danger of being

sunk.

Firstly, they would have been made aware of the

anomaly of being a British naval rating, in

uniform, aboard a foreign merchant vessel, where

it was obvious to the Admiralty and government

that we were breaking the spirit of the Geneva

Convention if not the actual code. And with that

would have been an awareness of how the Germans

viewed this and their refusal to accept any

British explanation of reasons for placing guns,

however defensive, aboard civilian ships.

Secondly, the implications in all this for Jack

were that, should he be taken prisoner, he may not

be treated very well, even treated very cruelly.

He may not be allowed the normal facilities that

prisoners-of-war under the rules of the Convention

were deemed to have a right to, such as access to

letters from home, Red Cross parcels and many

other things – including food.

Today, we can safely regard the German attitude of

that time as hypocritical in the extreme and just

a clever Teutonic bartering of words to justify

their own murderous intent and actions. Historians

now are very sure that both British and American

officials in government had already come to that

very same conclusion following German practices at

sea in the First War.

Jack's naval paybook would make no mention of “SS

Jack Carnes.” Officially, he was part of the

ship's company of 'HMS President III.” This was

partly to show, if captured, that he was a

bona-fide Royal Navy rating, on official business

for His Majesty's Navy, and his cap tally would

display HMS whatever ship he was on. But it was

also largely for pay purposes. There were hundreds

of DEMS gunners, serving on just as many different

ships, and for naval pay and accounting, it was

easier if all were considered to be part of the

same ship. This ship did actually exist, a former

WW1 corvette, converted essentially into a

floating office and moored in the Thames just

above Blackfriar's Bridge. She exists still,

albeit now decommissioned, and serves as a

historic-ship venue for wealthy businesses to host

conferences and corporate events. It is doubtful

if Jack ever stepped aboard her, or even knew

where she was. It's a sad fact that when scrolling

down the huge lists of naval ratings killed in

WW2, you will see 'DEMS' and 'HMS President III'

many, many times. There were hundreds like Jack -

volunteers all, heroes each and every one.

Just what would Jack have found when he first went

aboard the 'SS Jack Carnes'? From his own point of

view, to be drafted to an American ship, and a new

one at that, must have seemed to be some sort of

deliverance. Under training, he would have heard

endless tales of the hardships of new matelots

sent to serve on rustbucket smaller warships that

were tossed about like corks in rough seas, the

discomfort of crowded messdecks where hammocks

were close-slung by the dozen in rows, and the

hardships and filth endured by crews in the

regular task of coaling ship if one was

unfortunate enough not to get an oil-fired vessel.

Larger ships like battleships and cruisers may

have ridden rough seas better, but there was more

'bull', discipline, and a lot more observance of

strict rules of ancient naval etiquette. On this

American merchant ship, he would still be under

strict naval rules, but things would still be much

more relaxed than he could ever have hoped for.

Another point worth making is when we consider the

fact that he was just one of two Royal Navy

ratings aboard. Both would have come under the

jurisdiction of the senior American naval officer

aboard for his gunnery duties, and under that of

the vessel's captain for other matters. The senior

American gunner was a Petty Officer in the USN,

and it says a lot about both British men that

their service record to date, their bearing and

discipline, that they were trusted to be the only

Royal Navy ratings aboard and thus to represent

their service, and king, to the very highest

standards in all respects. Not something a lot of

folks would realise now.

We can be sure Jack would have marvelled at

conditions aboard this new American tanker. Not

that there would have been any luxury, for this

was a speedily built 'utility' vessel, the tanker

equivalent to the dozens of liberty ships American

shipyards were knocking out almost daily. Though

built to a basic wartime specification, there's no

doubt her American crew would have sought to make

her more than comfortable. Even her basic crew

accommodation would have been superior to their

equivalent pre-war British tanker of the same

size, and many times better than even the largest

British warships.

So no hammocks here, but proper bunks with

mattresses. As one of only two RN ratings aboard,

he may well have even had a cabin, shared with his

'oppo', unheard of even now for ordinary ratings

on British warships. A decent messdeck, with

plenty of tasty and homecooked food, is another

given. There were fridges in the smokerooms,

icewater machines in the messes and crewrooms.

Americans were not then, as now, known for liking

to live rough, willingly or otherwise. Extra

luxuries, like ice-cream, or the newly invented

fizzy, carbonated drinks that we now know as

Coca-Cola or Soda, would almost certainly have

also been available, though the USN was notably

strict on beer consumption aboard ships, and I

don't think there was a rum issue. Perhaps on this

merchant tanker, the rules were a little more

relaxed, but no master of Captain Merritt's

stature would permit any abuse of drink,

especially considering their cargo.

It is from the records that we know that Jack was

not alone. He had a British crewmate aboard, an

older man of 31 called Albert Farrow, who came

from Wellingborough in Northamptonshire. It is

likely they joined ship together, possibly even

from the same DEMS course. Their American Armed

Guard crewmates would have delighted in showing

off their more superior living conditions, on

every level, to these two 'Limey' sailors. For a

new and young British sailor, with visions in his

head of what he might have gone to, he must have

thought all his birthdays had come at once.

For younger folk reading this, who may be inspired

to learn a little more of what conditions were

normally like for RN ratings posted to serve on

smaller warships in both world wars, like

destroyers, frigates and corvettes, I heartily

recommend reading the most famous novel of the

time, “The Cruel Sea”, by Nicholas Montserratt. It

really is an eye-opener, and an unforgettable

picture of the hardships of Atlantic convoys in

foul weather.

Jack's new experience couldn't have been much

further from reality than that described in “The

Cruel Sea.” Not for Jack would days and days go by

without warm food, because small ships in stormy

weather had to have the galley fires extinguished,

nor being frozen with cold and perpetually soaking

wet, nor the ardous tasks of watchkeeping in

mountainous seas.

He would have been the envy of any of his

classmates when under training, or any of his

friends he was in touch with, had he happened to

mention what ship he was going to. But the

likelihood is that he would not have even

mentioned it to anyone, perhaps not even to Mavis,

though his excitement would no doubt have been

very great.

This American tanker was not built for speed

either. It is doubtful that she would have made

more than 15 knots on a calm sea ~ roughly

17-18mph. She had two steam turbine engines,

geared to one single screw. The wartime

requirement for new merchant ships was for two

speeds, those to be able to make 12kts for slow

convoys, and 20kts for what were laughingly called

fast convoys.

Displacing just a little under 11,000 tons, she

was for her time and type considered a large

vessel, albeit dwarfed by the massive leviathans

we see today, regularly now at over 100,000 tons.

Next to a battleship or aircraft carrier, a 10,000

ton tanker was the next prime target of any u-boat

commander, and top of the merchant shipping list

of targets along with ammunition ships.

She was of the slower speed, but at 15 knots, she

would be considered just about capable of

outrunning a u-boat on the surface, but could

certainly outrun any submerged. We know now that

in the event, she very nearly did. To successfully

hit a ship with a torpedo at 15kts, from perhaps a

mile or two away required, in essence, for a

submarine to lie in wait, take very careful aim,

and hope for the best.

The ship sailed from her Welsh port on the 25th of

August. It would take almost five days for the

'Jack Carnes' to make her way from south Wales out

into the north Atlantic, heading roughly south

west through the already heavily U-boat infested

waters of the Western Approaches to her last known

position, just north of the Azores. Running a bit

lighter, even with water ballast, she could have

been a little quicker too in covering the roughly

1,500 miles. She was also sailing independently,

not within an escorted convoy, and indeed, the

record shows she had never been in convoy, on

either side of the Atlantic.

Late August would have been reasonably nice,

weather-wise, and as they journeyed south west,

the sea would have got even more blue and the

temperature would have climbed even further. All

in all, as Jack took in his new surroundings and

role, he would have looked forward to the voyage

ahead and seeing foreign climes. We can well

imagine him lying on his bunk at night, after a

fulfilling American meal, which wouldn't have been

short on meat, hardly able to believe his luck,

and thinking, 'this is the life.'

There are numerous websites that detail the loss

of the 'SS Jack Carnes', some with a crew list, or

listing the casualties of the incident. Some

details vary in minor ways, but piecing them all

together, we now get some idea of what happened,

what took place, and also what can be discounted.

During the morning of the 30th August, the ship

was maintaining a zig-zag course, the appropriate

method to avoid being prey to a torpedo. The

accepted practice was not to keep to the same

course for more than ten minutes, then alter

course 10 degrees or so, to port or starboard

alternately, but at the same time maintaining a

general heading in the direction they wanted to go

on a gently weaving course. At 08:00hrs, they were

roughly 200 miles north of the Azores, and still

generally heading south-west.

What happened next is gleaned both from the

accounts of the American crew, and from German

records and reports they submitted later.

One u-boat, U-705, was indeed lying in wait. The

submarine fired a spread of four torpedoes, but it

appears that the tanker was not hit on this first

occasion. The submarine then surfaced, and from

about 5 miles away, started shelling the tanker

with her surface mounted deck gun. Around 10

rounds were fired, but none directly struck the

ship, though they were close, with shrapnel being

scattered over the deck.

By now, the crew would have been called to action

stations, and the master, Captain Merritt, would

be directing his crew's responses from the bridge.

Within three minutes, all gun crews would be

closed up, just as they would be on a warship. At

the same time, the radio operator would

immediately have started sending desperate mayday

signals to tell that they were under attack. The

captain would have rung down to the engine room

for the chief engineer to open up the engines and

make as much extra speed as he could muster to

open up the distance between them and their

attacker. But in truth, she was probably not far

off full speed anyway and couldn't have gone much

faster. Jack would have quickly turned to, helping

to man whichever gun was his action station.

There were two larger guns carried, one 4-inch and

one 3-inch, plus some smaller calibre machine

guns. I suspect Jack would be on the 3-inch gun,

which records say was mounted on the large

circular mounting on the ship's bow, along with

his RN messmate, working together. The Americans

would perhaps have took the slightly larger and

more powerful gun mounted on a similar large

mounting over the stern, behind the crew quarters

and aft superstructure. Other American guards

would have been ready at the machine guns for a

close-quarter fight if required.

The gunners between them fired eight rounds from

the forward gun, and 13 rounds from the after

4-inch gun. Either way, we can assume that Jack

did get to crew a gun that fired in anger and do

what he was trained for. Their gunnery was

obviously effective, for they forced the submarine

to submerge. With only one deck gun, the enemy sub

was effectively outgunned, and now in a very

dangerous position herself on the surface.

In essence, they had won their first battle. The

tanker's crew would have been both euphoric, and

at the same time, apprehensive. The sub was now an

unseen enemy below the waves, and all they could

hope for was to outrun her. This first battle may

have been won, raising hopes, but sadly, their

hopes were to prove misplaced.

Uknown to them all, the u-boat that they had

beaten off had signalled to another u-boat further

along the “Jack Carnes” zig-zag path. This u-boat,

the U-516, sighted them passing going at full

speed, and so a frantic chase ensued. The u-boat

chased after them for no less than 270 miles, over

a period of 18 hours. The 'Jack Carnes' with it's

American and British crew very nearly did get

away.

By later that evening, the whole crew must have

thought that they had successfully escaped

disaster, at least for now. But luck was not with

them. In the early hours of the 31st, just short

of 2am, the chasing u-boat caught them up

sufficiently enough to get sight of them in the

moonlight, take aim and stealthily fire two

torpedoes, one of which struck the 'Jack Carnes'

on the starboard side just forward of the bridge.

The chase was over.

Miraculously, although their ship was now

seriously damaged, no crew were killed or injured

at this point. Once again, the klaxons of 'action

stations' would have sounded. Considering what had

happened earlier, it is likely half of the gun

crews were already closed up, taking it in watches

to have at least one gun manned constantly. Within

a couple of minutes, all the other guns would be

fully manned too.

The master had ordered the helm to be swung to

starboard, to face any other oncoming torpedoes

and present less of a full-length profile, but the

watch below erroneously secured the undamaged

engines and the ship lost way. Four minutes after

the first hit, the u-boat fired a torpedo which

struck on the port side in the No4 tank, followed

by a coup-de-grâce which struck the starboard side

amidships.

The nine officers, 33 crewmen and 14 armed guards

then abandoned ship in two lifeboats. A fifth

torpedo was then fired by the U-boat, which struck

the starboard side aft of the midships house, a

sixth hit the starboard side bunker tanks and a

seventh struck amidships

The captain and officers would realise straight

away that those first few hits meant the game was

up, and that they would ultimately lose the ship.

Luck was with them again insomuch as there was no

fire, for even an empty tanker can be something of

a torch if oil fumes in the storage tanks were

ignited. What did happen was that the total of

five explosions in her hull weakened her structure

so severely that she 'broke her back', she

effectively broke in two, and started to sink. Her

last known position was at 41.35 N - 29.01 W.

Once the order was given to abandon ship, the two

large lifeboats were launched successfully, and

all the 58 crew got away fairly swiftly from their

stricken ship. Their job done, the u-boat

submerged, and simply slipped away. The crew were

only able to sit in their lifeboats at a distance,

and just as dawn was breaking, at about half-past

four in the morning, watch as the bows of the

remaining half of their vessel rose into the air

and quickly slipped beneath the waves.

The crew were divided evenly between the two

lifeboats, 28 men in each. Eight of the Armed

Guards, and the two DEMS gunners, Jack and Albert,

along with the master, Captain Theodore Roosevelt

Merritt, and three officers were all in one boat,

and the rest of the officers, four more Armed

Guards and civilian crew were in the other. The

sea was evidently fairly calm to start with, and

the crews roped both boats together.

What happened next was described by some of the

survivors, including the ship's chief engineer, a

Henry Billitz. He tells that during the night,

(maybe the same night or the next, we don't know),

a storm blew up, which brought 50 to 60 foot

waves, and the line between the boats parted, and

so they drifed apart. The chief says that he never

saw the other boat again.

The remaining lifeboat gradually drifted south, no

doubt assisted by some fervent rowing, and after

six days spent in an open boat at the mercy of the

weather, they thankfully made landfall on Terceira

Island in the Azores on September 6th. It was here

that they apparently learnt that, three days

earlier, a Royal Air Force flying boat had

attacked and sunk with depth charges the very same

u-boat that had torpedoed the “SS Jack Carnes.”

The survivors took some comfort from the

additional information that the u-boat was lost

with all hands.

Jack and Albert were never seen again, and nor

were any of the other 26 men that escaped the

initial sinking. Given the rough seas that came

later, we can only speculate and hope that their

end would have been mercifully quick, and that

their boat was swamped and overturned and all were

drowned.

It is unlikely that they drifted for several days,

as was the fate of many a ship's crew in wartime

when forced to take to the boats, to eke out ever

diminishing rations and water only to eventually

succumb to starvation, thirst, and the burning

heat of the sun.

The curious thing about Jack's loss is that Mavis

could not accept his loss at all, not for several

more years. She always harboured the hope that he

had somehow survived the sinking and would one day

return from the war. Such miraculous returns of

men long thought to be dead were not unknown, and

many a supposedly lost sailor did indeed fetch up

on foreign shores somewhere, often badly injured

and nursed back to health by locals, only to

return out of the blue some years later to the

surprise and delight of his grieving family. It

had been known to happen.

Finding out so much more detail now, over 70 years

after the war finished, tells us the tragic truth.

That Mavis' instinct, her long held belief that

Jack had survived the torpedoing, indeed, had also

survived the sinking, was correct all along. His

family at the time, his parents and all Mavis'

three sisters, now long dead themselves, would

have been astonished to learn all this today. She

was not wrong to hold out such hopes, for it very

nearly did happen. The fate of an unseasonal

mid-Atlantic storm ultimately robbed Jack of his

life, and both of them of what might have been.

By the time she received the dreaded telegram,

within a week or so of the sinking, initially just

posting Jack as 'missing', she had discovered

something else - Mavis was expecting Jack's son.

The tragedy was now compounded by, not just his

grieving widow and his own family, but also the

expectation of a fatherless child.

Michael was born early the following March, and

grew up always knowing of his dead father's

sacrifice,

but also aware that he

was not unusual either. For many other boys had

also lost fathers in the war, and going through

his school years, he would have known of several

in a likewise position to himself. By the time the

lad was about eight years old, we think Mavis was

beginning to accept that Jack was indeed lost and

would never return. I think that Michael, who

himself died as a result of a heart attack aged

only 42, would have taken great succour and

comfort to know of the small role his father had

played in Britain's defence, had all this

information been available to him. but also aware that he

was not unusual either. For many other boys had

also lost fathers in the war, and going through

his school years, he would have known of several

in a likewise position to himself. By the time the

lad was about eight years old, we think Mavis was

beginning to accept that Jack was indeed lost and

would never return. I think that Michael, who

himself died as a result of a heart attack aged

only 42, would have taken great succour and

comfort to know of the small role his father had

played in Britain's defence, had all this

information been available to him.

It was not until almost ten years after Jack's

death that Mavis would find renewed happiness when

she married Percy Wardle, a bus conductor, then

working for the Midland Red. They met whilst she

was working at a cafe in the centre of Coalville

much frequented by bus crews. Mavis' next eldest

sister, Edna, had also met her husband, Gordon

also on the buses, whilst working at Chad's Cafe,

just a year or so before the war.

Writing this now, I also wonder whether her

sister, or even brother-in-law, had some hand in

that meeting,

a sort of guidance.

Perhaps there was some gentle encouragement from

Gordon advising Percy to bide his time. Both were

conductors working out of the same depot, so both

knew one another. Edna had met her husband at

Chad's Cafe, so why not Mavis? a sort of guidance.

Perhaps there was some gentle encouragement from

Gordon advising Percy to bide his time. Both were

conductors working out of the same depot, so both

knew one another. Edna had met her husband at

Chad's Cafe, so why not Mavis?

They married in the summer of 1952.

Edna and Gordon already had a three year old son,

Alan, at the time of Jack's death, and then

Rodney, another cousin to Michael, would be born

later in 1942, just after Jack's loss and just a

few months before Michael himself the following

year. In later times, the three growing cousins

would become almost inseparable, as Mavis drew

particularly close to Edna, five years her senior,

and her two boys.

In Percy, the beloved uncle of my own memory,

Mavis found herself a real gem, and they married

in the summer of 1952. Percy became the loving

father that the fates of war had robbed Michael

of, and Mavis did then have several happy years as

a wife and mother, bringing a new brother to

Michael into the world when Phillip was born in

1954, giving Percy his own son.

Now the past could be better laid to rest, but

Jack was never forgotten, and never would be. It

is to Percy's credit, kind and gentle man that he

was, that he helped to keep Jack's memory alive

for Michael. The rest of his cousins, Sylvia's

boys, were always aware of 'Uncle Jack' and the

sacrifice he had made and what his loss had meant

to the family, and particularly to Aunt Mavis

herself.

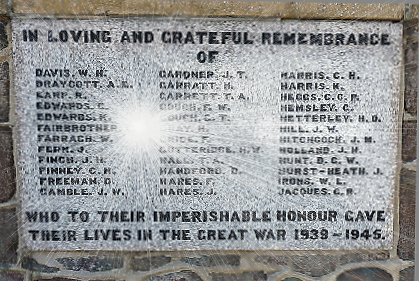

Whenever we visited Coalville to see either set of

grandparents, or aunts and uncles, whether

returning to Leicester by bus or train, mum would

always drag us boys by the hand up the steps of

the Coalville Clock Tower War Memorial to see

Jack's name carved into one of the stone plaques

listing the dead of Coalville from both world

wars.

Whenever we visited Coalville to see either set of

grandparents, or aunts and uncles, whether

returning to Leicester by bus or train, mum would

always drag us boys by the hand up the steps of

the Coalville Clock Tower War Memorial to see

Jack's name carved into one of the stone plaques

listing the dead of Coalville from both world

wars.

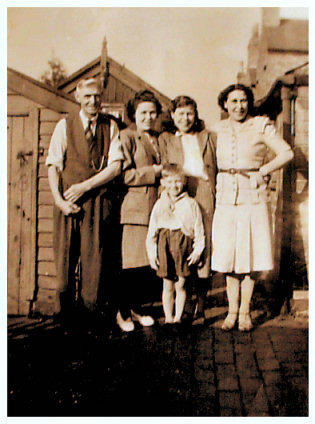

Mavis, in happier times, standing next to her

dad, alongside two of her sisters, Sylvia and

Edna, and young nephew Alan, c.1946. We think

her eldest sister, Gladys, took the photo.

Sylvia was only 12 when Jack was lost, and the

circumstances of not quite knowing what happened

to Jack, plus her sister's grief, indeed the grief

of the rest of the family, following on so closely

after their own mother's death, made a massive

impact on her and Mavis' other two sisters.

The tragedy for the family of this Second War loss

of Jack was that, in some ways, it cruelly

mirrored a similar family wartime loss on the

girls' mother's side during the First War. Their

own mum's brother, Uncle Lakin, had been in the

army, and ultimately died through being gassed.

Lakin Manderfield was also an uncle to all four of

the Holt girls, just as Jack was an uncle to all

the Holt grandsons, including myself.

Coincidentally, Lakin's own son was also killed in

the Second War, in 1943, serving with the Royal

Artillery in Liverpool. It was indeed a terrible

span of three years of successive tragedies

affecting the Holt family.

To all of the Holt family, the victory when it

came in 1945 must surely have been very

bitter-sweet indeed. As the nation celebrated,

widows all over the country and empire mused on

what that victory had cost, and Mavis, bless her,

still thought, prayed and hoped, that she may not

be a widow after all, and Jack may well just walk

through the door.

But it was not to be. By the war's end, Mavis

already had the second letter from the Admiralty

informing her that her husband, previously listed

as missing, was now officially, 'missing, presumed

dead', and now actually listing the name of the

ship he was actually serving on. So Michael always

knew his father had been serving on an American

ship, a tanker, which must have puzzled him all

those years ago just as it puzzled me.

Even then, for several more years, she still

harboured hopes of a miracle. But somehow, the

fates conspired against her again and again, and

gradually took all those she loved most dear, one

by one, her second husband, both sons, and all her

sisters before her.

For incredibly, after only some 25 years of

marriage, Mavis would be robbed of Percy also,

when an industrial accident at work caused him to

lose a foot, which then turned gangrenous and, in

1975, ultimately cost him his life too. Jack's

son, Michael, aged only 42, would himself die of a

heart attack in 1984. Even more incredibly, only

15 years later, Percy's son and Michael's younger

brother, Phillip, would also succumb to heart

disease when aged only 46, and leaving three

children.

Mavis, left, enjoying a cuppa with sister

Edna in later years

Much of this later information, the extra details

about the actual attacks and the sinking, how the

boats were separated, was only discovered by

virtue of the internet in the last 10 to 15 years

of Mavis' long life. It first all came to light by

discovering an Armed Guard veteran's site, written

by one of the survivors in the other boat. It

would have been cruel to tell her, then aged well

over 80, that her initial instinct, that Jack had

indeed survived the sinking, was correct after

all, and that cruel fate and a strong wind had

conspired to prevent his homecoming. So she never

knew.

Now, with her passing, and the last of the

generation of Holts and Hills that were affected

by these events, the full story can be told for

the benefit of the rest of the family who are

interested enough to read it. But moreover, to

keep alive the memory of two things.

Firstly, of one man's sacrifice amongst so many

others for their country in time of war, and

secondly, of one woman's undying love and belief,

her faith and fortitude, to carry unbelievable

burdens of grief as the loss of one family member

after another befell her, her two husbands and

then her two sons, losses that would sorely test

her faith and resolve over the years. Mavis always

said, in that last few years and particularly

after her last sister, Gladys, died in 2010, she

never wanted 'to be the last one left'. And after

so much loss, we can well understand that now. But

the fates once again conspired against her, and it

would turn out to be so. Despite everything, our

Aunt Mavis never gave in to self-pity, nor to any

bitterness. She really is a hard act to follow, in

every sense.

Jack's death is recorded in several places, of

which at least two are war memorials. The Clock

Tower War Memorial in Coalville, and the Royal

Navy memorial at Portsmouth, on Panel 64, Column

1. And of course, now online on various websites,

not least of which is the Commonwealth War Graves

site, none of which actually mention the 'SS Jack

Carnes' by name, only that Jack was 'aboard' HMS

President III, that psuedo-fictitious payship

moored in the Thames.

Hundreds of men are similarly listed as HMS

President, most were DEMS gunners and volunteers

all, and it's still true that many of their

families, even all these years later, know nothing

of the actual ship on which their relative was

lost, nor of any deeds in which their men may have

taken part. Though, for those curious enough to

enquire further, it is now possible to find out

most of what is to be found without even leaving

an armchair.

Almost a million men alone served in the Royal

Navy during the war, five times the number serving

when the war started. In total, 81,000 sailors of

both the Royal and Merchant Navy lost their lives

during their service, both at sea and ashore, or

as prisoners of war.

To be a naval rating on a warship was dangerous

enough, though it could have its rewards and

occasional periods of excitement. To be any sort

of rating on a merchant ship was highly hazardous

in the extreme, and was for the most part very

boring. When merchant ships were attacked by

warships, or aircraft, there was usually only one

outcome. Jack's role was to try to make that

outcome just a little less likely, and as we have

seen, most outcomes were not good.

Mavis with son Michael, c.1947

Mavis with son Michael, c.1947

To the memory of Jack, and of Percy, and their

sons,

Michael and Phillip, and not least, Mavis

herself. R.I.P.

one of the memorial plaques on Coalville

Clock Tower,

one of the memorial plaques on Coalville

Clock Tower,

'Our Jack' listed on the right as 'HILL J.W.'

a link to Jack's memorial page on

the

Commonwealth War Graves Commission Website

listing his details on the

Portsmouth Naval Memorial at Southsea.

|

|