BEGINNINGS:

What makes a boy, a young lad, want to 'go for a soldier',

as songs of the day often put it. To understand Harry's

possible reasons, for it's all speculation and no one can

now be entirely sure, we need to understand his time.

He was born a Victorian, in 1893, but grew up an Edwardian.

He would have been aged 8 in 1901 at the time of the old

queen's death and the ushering in of a complete new age, as

well as a new century. What was going on during those

formative years? The immediate and obvious answer is, The

Boer War, taking in those years from when Harry was about 6

to when he was 9 or 10. And before the Boer War, stories

told by old timers of the times of General Gordon, the siege

of Khartoum, and even further back, the Indian Mutiny, were

in abundance for any lad that wanted to listen.

There were all sorts of influences on a boy; other boys, old

soldiers related to or known to the family, and not least a

boy's own parents. It was not common for a mother to

actively encourage soldiering in any lad, though it has to

be said that when that choice was made, a mother would often

be as proud of her son as any father. I've no idea whether

Harry's father, my great-grandfather Charles Holt, had some

or any influence on his son in either direction. But we can

make a pretty shrewd guess as to what Harry's choices were

for future employment, or for any lad in that district at

that time.

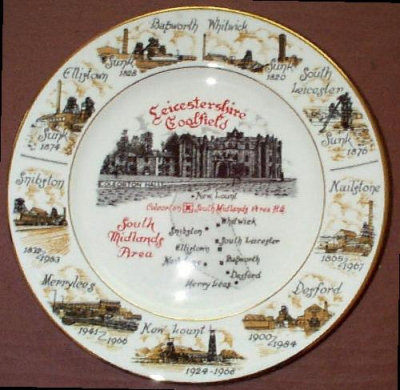

To sum up, there were four choices. The easiest and most

obvious, and most commonly taken too, was to be a miner, as

was his father. There were almost a dozen mines within the

immediate Coalville and Whitwick areas, employing thousands

of men. If that was what a boy really wanted, and many did,

he could go 'down pit', like his dad.

I haven't gone deep enough in Charles' story to know whether

he served in the military or not, but we can be sure that

once his son was aged about 10, with the end of schooling

getting ever closer, he would have impressed upon his son

both the benefits and drawbacks of working underground.

Harry would also have seen and heard some of these for

himself, and heard the conversations and been aware of the

week-to-week financial struggles of life down the pit. He

would also have been aware that boys, and girls, as young as

he was then, had been forced to work underground within

living memory, the days of wider use of child labour in all

industries not all that long passed. As to the dangers, they

were ever present in local overheard conversations, not

least the recent Whitwick pit disaster in 1898, a week or

two before Harry's 5th birthday. I feel there would be no

escaping local chat, looks in the street, the general news

and air of grief and despondancy, even for a 5 year-old.

Harry would have known well the dangers of working

underground from a very early age.

To avoid that, there were perhaps three other obvious

choices. First of which was to get a job on the land, a

local farm, and be a farmhand, perhaps with a view to

promotion to a cowhand, pighand or even ploughman. Indeed,

his older brother had done just that at first, but he still

went down the pit when old enough. Poor renumeration as it

was for the danger and the shifts, it was still where the

money was.

Another local choice would be to get a job in one of the

many hosiery, knitwear and sock factories abounding in

Coalville at the time. There were also some shoe factories,

in the main for ladies shoes, but most of the work in all

those places was filled by women. Becoming a mechanic and

maintaining the increasingly complicated factory machinery

would be the best a boy could hope for in that area, one

that needed a decidedly mechanical turn of mind.

A further choice would be to move - to the big town. In

Harry's case, he had a choice of three or four almost

equi-distant, all booming industrial towns of their day.

Both Coventry and Derby were near enough, and Loughborough

had a growing bell foundry and electrical industries. On the

question of factories of all sorts, all were heated by

steam, ie, coal, and all had boilers that required

boilermen, and stokers to feed those boilers. But the most

obvious choice was the county town, just 12 miles away,

Leicester. And many did make that choice. That is exactly

how my paternal family came to leave that same area and move

to that town around about that same time.

The final choice, invidious to a boy's mother, was to go for

a soldier, or even worse, become a Jack Tar and go to sea.

To join 'the forces', albeit there were only two to choose

from. But to a father, already a miner and very conversant

with the dangers therein, soldiering was not such a bad

choice. At least it was out in the open and under the sun,

and one could argue that any dangers were of equal balance,

a simple choice: to be killed underground by being gassed or

a rockfall, or killed above ground by a bullet or bayonet. A

no brainer, we'd say.

TO BE A SOLDIER:

So it was that, in 1911 and as soon as he was 18 and

eligible to serve, Harry joined a local unit of the

Territorial Forces. What later became the Territorial Army,

our TA of late memory, the Territorial Forces were Britain's

army reserve, trained for both local defence as well as with

a view to any necessary foreign service. Most county

regiments had a TF component, one battalion which was

composed of part-time soldiers who lived at home, issued

with hand-me-down and obsolete weapons and kit, and still

had ordinary civilian paid employment.

In Harry's case, that employment would be at the mine. He

would have the best of both worlds, be a miner for as long

as he could stand it, whilst also being a part-time soldier

and retain the option of joining the colours full time. The

1911 census shows him employed as a 'pony driver -

underground', and living at home in Highfield Street. He

worked at South Leicester Pit, which was in fact at

Ellistown and just south of Coalville. His elder brother,

Bill, was listed as an 'ag lab' - ie, working on the land,

on a farm. Being in the TF brought other benefits; free

holidays. Summer camps, military exercises and route marches

may not be regarded as a free holiday now, a miner working

underground - who didn't earn enough to afford going away

for annual holidays - 'going on camp' was literally a breath

of fresh air, plus he went to places he would never have got

to otherwise. And it carried some 'street cred' for any lad

back in the day.

We know nothing more until 1914, in the spring of that year

when he married Violetta Manderfield, a lass from over

Shepshed way, at the little 'tin tabernacle' further down

Highfield Street. Where and how they met, as is often the

case with most of our grandparents, we have no idea.

Shepshed is over 'the forest', halfway over to Loughborough

and outside of the immediate mining areas of Coalville and

Whitwick. Indeed, those two towns are at the northern end of

the coalfield which stretched mostly

southwards

as far as Bagworth and Desford. There were certainly plenty

of pits that Harry could have found work in, perhaps the

nearest not more than a couple of miles away over at

Snibston, a little way down Ashby Road in Coalville itself.

For three years, now Private Holt, 4872, trained in

soldiering on occasional weekends, plus an annual fortnight

compulsory camp somewhere well away from home, with the 5th

Battalion of the Leicestershire Regiment, a Territorial

Forces reserve battalion.

We can assume he learnt how to wear his uniform, march and

drill, do basic ceremonials, as well as learn the rules of

handling rifles and go some way to being as good a marksman

as his eyesight and nerves would allow.

To that end, given his later trade as a Lewis gunner, we

also have to assume there was nothing wrong with his eyes

nor marksmanship. His record shows that, shortly after the

start of his service in the following year, he attended the

summer training camp at Aberystwyth. The date curiously

enough, 4 Aug 1912, exactly two years to the day before

England and her history was to change forever.

Come that fateful day, which we all know the date off by

heart, as well as a good many of the events on that day both

in London and around a feverish nation, we also know that

the actual declaration of war was late that night, at 11pm.

It would be the next day that national headlines would

proclaim on hundreds of placards in one fateful word, "WAR".

The nation became animated almost as one, and thousands of

young men, some much too young, and some older ones too,

flocked to barracks and recruiting centres in every town and

city to sign on into the king's service.

As did Harry, for his service record shows him 'attesting'

into the Leicestershire Regiment on 5 August 1914. He must

surely have been in the mass of men flocking to the colours

and almost crushed in the rush. The nation's anger as well

as disbelief at German affrontery to attack a neutral

country was heightened as news quickly came in of most

definite atrocities, the cruel killing of women and

children.

Of course, we know now that the attack on Belgium was merely

a means to an end; Belgium was not the real target, which

was namely, to attack and invade the French.

But no matter, those early news reports, plastered on

newstands and carried swiftly by rail to the ends of the

country the same day, animated folk to almost hysterical

proportions. We have to remember, there was no radio news, a

national broadcasting service still a long way from being a

reality. The BBC itself was not formed until 1922.

Harry, and his friends, were caught up in all that. By now,

he was aged 20 and newly married. What Violetta thought of

his rush to go to war, we don't know, but she had married a

soldier, and we must assume she was proud of him even if not

fully amenable to the prospect of extended periods of

separation. Also, they had now moved into a home of their

own; well, a rented home of their own.

Just up the street from where he had lived with his parents,

but back towards Coalville, a new terrace of cottages had

been built in 1904, called 'Oak Grove Cottages'. Only 10

years old, they were in terraces of eight, divided by one

covered entry right in the middle. Harry and Violetta now

took possession of the first house on the left hand side of

the entry.

Each house had a water supply - a pump in the kitchen -

mounted on a low-level enamelled sink, though as it

happened, there was a communal well at the back also. Later,

when no longer required and more of a danger than an asset,

grandad would cover that well and build his shed over it.

There was also an outside loo, one to each house, something

else of a luxury at the time. It was a modern 'flush' loo by

the time I knew it, though I suspect it was a lot more basic

than that when those cottages were first built.

The kitchen had a little extension, a cold pantry, with a

tiny window paned, not with glass, but a fine wire mesh. The

place was like a fridge in winter, before fridges were

invented, but still cool in summer - the whole point of it

really. In the corner of the kitchen itself opposite the

sink, a raised brick plinth across the corner, underneath

which a fire could be lit which served to heat up a copper

boiler standing above.

That was in 1914, and believe it or not, that is much how

the arrangement was in 1955 from which my earliest memories

stem. It was where my mum and her three sisters were born

and grew up, and both my grandma and grandad died. A real

family home, with the usual mix of both happy - and tragic -

memories.

Being new, and Highfield Street not having been built up as

continuous housing down both sides, there were as yet no

house numbers. The postman knew everyone, and each house had

a name, or was part of a row that had a name. So it was with

Oak Grove Cottages, and being new and with no number, it led

to some confusion with the military authorities about his

address later. On his records, this is clearly given, and we

that know the area knew what it meant. Later, it would be

allocated a number ... 208.

But that confusion, I believe, may nearly have got him

arrested later when his final call-up came, as his official

letter calling him for a medical in London was addressed to

'Oak Street', and there being no such street in Coalville,

the papers were returned to the War Office. On which point,

minor panic set in with officialdom, with letters too and

fro to trace him that have actually been preserved amongst

his records. The end result was he had much less notice to

'mobilise' than he should have. But that came later. It's a

wonder he didn't find Redcaps come looking for him.

"IT'S WAR" ~ "BRITAIN AT WAR" ~ "FLEET READY"

The German attack on Belgium, abhorrent as it was, had not

exactly come out of the blue. This war had been brewing, and

looming larger for some time, some years in fact, and there

had been plenty of time to prepare. Local history tells us

that on that first full day of the war, 5th August, there

had already been a huge tented encampment of the

Leicestershire Regiment at Whitwick, in the fields below the

woods on Loughborough Road.

It was to here that the youth, and not so youth, of

Coalville and Whitwick headed to enlist in the king's

service, and here too went Harry and his friends. As an

existing member of the regimental reserves, he may well have

not quite expected the knock-back he gained that very day,

purely on account of his job.

For his offer to serve, at least in the short term, was

refused, and he was duly sent back to his work. His

attestation sheet shows his original dates of joining the

TF, in 1911, and then shows his further attestation to join

the regular army as on the 5th August 1914. In effect, he

was told, 'thank you, but not now son, we need you at home

digging coal'. And that would have been a truth he could not

argue with, and no doubt quite a few other young local

colliers had the same result. Also, being a newly married

man may have had something to do with it. I think Violetta

may have been much relieved when he returned home,

chastened, a bit put out by rejection, but safe . . . for

now.

There were lots of reserved occupations, mostly in essential

industries and services, and once a man was designated as

being in such a job, it was almost impossible to

re-designate that job and escape its clutches. For men that

didn't want to fight, or didn't have the required degree of

belligerance and who were just not up to soldiering, a

reserved occupation was verily a godsend.

For those that were keen, did want to go and fight and

serve, it was nothing more than a trap. Coal mining was one

such trap. In the early days of trench warfare, and into

1916, digging under an enemy's trenches became a popular

means of attack, by tunnelling and laying huge explosive

charges to blow whole sections of enemy trenches to kingdom

come. To this end, former miners, and a few brought from the

English and Welsh coalfields, were recruited into the Royal

Engineers for that very purpose. But that came much

later.

For now, for Harry, his consolation was that it was a given

fact that this war would be over by Christmas. The fact was

plastered all over the press. Everyone believed it.

Of course, we know now that the war was not over by

Christmas, or the next Christmas nor the one after that.

1915 came and went, and one defeat or setback followed

another. But Harry had to keep at his underground work.

By early 1916, the war was going very badly and had become

the very static and bogged down trench warfare we now know

so much about. For Harry, nothing much had changed, other

than he was now a father, his first daughter Gladys being

born at the end of the previous October, in 1915. In some

ways, his chances of breaking his mining bonds and getting

away to the war were now just ever so slightly a little more

remote, though the numbers of young married men with a child

or two being taken into the army and becoming casualty

figures were now becoming rather alarming. By late 1916,

increasing shortages of troops, caused by ever increasing

casualty lists, saw laws passed to press men into the

nation's service; conscription had come in. The war effort

was not yet desperate enough to warrant calling up reserved

occupations in order to defeat the Germans.

CHANGING TIMES:

April of 1916 would bring a surprise Harry hadn't bargained

for. He was 'transferred' out of the Leicesters, to the

Royal Defence Corps, a sort of WW1 version of the Home

Guard. He was now in the 156 Protection Company, RDC, with

its HQ at Donington Hall, up near the county boundary west

of Kegworth.

I think this transfer would have come as something of a

shock. To be debadged from your home county regiment, into

something seemingly a lot more mundane and commonplace, is

no small thing. He had spent over 4 years learning about

comradeship and loyalty, and building up a considerable

amount of regimental pride. All that was seemingly set

aside, and despite his soldierly yearnings, he was pushed

aside and downgraded to local militia.

The fact that I can say that, with some degree of certainty,

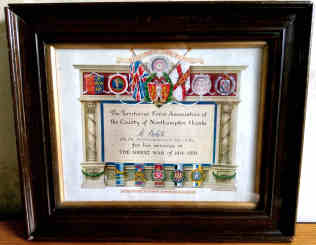

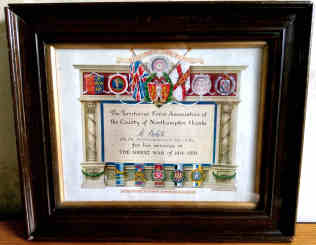

is because of 'the picture', the framed picture of himself

that hung over the sideboard from roughly this time until

his death in 1972. It is I believe a pencil drawing, done at

some expense, and framed at even more expense. This image

online does not do it justice, for it is huge, like a very

large portrait mirror that would hang over a fireplace, and

does not here show the large, partially gilded frame. The

image of Harry in the oval, in his khaki complete with

peaked cap, is surrounded at the four corners by

unmistakable images of empire. Coloured drawings of HM The

King, Lord Kitchener, plus a Field Marshall (probably Sir

John French) and an Admiral, (probably Admiral Jellico) all

bedecked in the crossed flags of the Union Flag and the

Royal Standard. Was this Patriotic, or what? I have that

picture now, a treasured possession, hence this photo of it.

I believe the picture was done not so long after joining the

TF. His cap badge is unmistakable as that of the Leicesters,

the 'Tigers' as they're colloquially known. The pride in

regiment, and himself, oozes down on the viewer, and so it

did in that little back room in Highfield Street. But in a

way, having that picture done as it was, at that time,

whoever commissioned or paid for it, was that a little bit

of his undoing later. But that is some way into the future.

Harry's transfer to the RDC came right at the end of April,

and the next entry underneath that is dated 1 Oct 1916. In

more faded but still readable ink, it states, "Remaining in

Class 'W' TF Reserves as long as is necessary to retrain him

in civil employment." So no sign of any call 'to the

colours' as yet then.

I'm pretty sure Harry never saw that, for a man would never

get to see his own record, written up from all sorts of

forms and despatches from his own battalion headquarters and

sent up to London to be entered onto his own growing folder

of sheets and forms.

That was one of the many jobs of every battalion adjutant

and his office, with his little army of clerks, writing and

typing up records and sending them on to the War Office to

be kept in perpetuity. In the civil world of industry today,

that part of the adjutant's office would be called 'Human

Resources'.

So, despite the disasters of 1916, the setbacks and losses

of The Somme, he was still not to be called. By that time,

the numbers of men from all districts of all towns and

cities lost, listed as killed or missing, were horrendous.

Typed up lists were sent almost daily to individual towns to

be posted on town hall or civic hall notice boards, where

after every major battle, crowds would push and shove to get

close enough to discover who were the latest neighbours and

friends that had lost boys at the front. Widows and bereaved

parents would have already had the dreaded, black-edged

telegram telling of their worst possible news.

Harry, out and about in Coalville when not working, as would

Violetta when out shopping, would be very aware of these

lists and felt those losses as keenly as anyone else. He

would have been familiar with the Coalville Times, their

local rag, as well as the Leicester Mercury, and their

endless lists of the even greater losses being suffered in

that city and county wide.

He would also have been aware of the civic pressures on men

to sign up and serve, and undoubtedly he would have had a

little badge to wear on his jacket collar to signify that he

had signed up, and shown willing, and therefore most

definitely would not be deserving of the dreaded white

feather. Because of his TF service, coming and going

from parades in uniform, he would have been well known as a

keen soldier, but many of those neighbours were also mining

families. I doubt he was ever at risk of being deemed

worthy of a white feather.

So it was locally, in a mining town, that so many men who

were of an age and fitnest to serve were being held back

that he would have been nothing unusual. A casual observer

in Coalville market place on a typical nice Saturday in 1916

may have been forgiven for doubting that there 'was a war

on' at all, the place would have been full of miners old and

young.

For Harry, the next thing we see in his documents are the

little typed letters and forms concerned with recalling him

from Class 'W' reserve and the mix-up over his address. We

entirely miss out 1917, during which of course, the war and

its figures simply go from bad to worse, in every aspect, on

land and at sea. And by now, in the air too. The war was

more bogged down than ever, the front line hardly ever moved

and when it did it was at great cost in lives whether going

forward or back.

So I do have some suspicion now whether Harry was quite as

keen on soldiering by Christmas of 1917 as he had formerly

been as a teenager and then newly married man. He must

surely have been in a cleft stick, between a rock and a hard

place. Torn between duty to his country, to his regiment,

and duty to his wife and daughter, he would have reflected

on yet another major impending change in his circumstances,

of yet another baby.

Violetta would be in the end stages of her second pregnancy,

to Edna May, born at the end of January in the new year of

1918, and her birth given some pause for thought. Harry may

well have come to the view that whatever happened now,

however badly the war went, he would be going nowhere. But

events were conspiring against him, or for him, depending on

what view we take of his overall feelings at the time. We

can only surmise.

1918 came in, with a country totally despondant about the

course and state of the war. Whilst defeat was still largely

unthinkable to many, few seemed to think that it was a

winnable war either. A growing number had come round to the

view that the best we could hope for was a truce, some sort

of unpalatable settlement that would at least halt the

killing. Rationing had come in the previous year, we'd had

conscription since the year before that, and ever more young

men were called to the colours as they came of age to serve,

many of whose names would shortly appear on those casualty

lists. Through it all, Harry continued mining.

MOBILISATION :

Now we arrive at some very significant dates, the first of

which is 21st March 1918. This is the day of the first of

three serious 'big pushes' by the Germans on the Western

Front. Serious enough to take more territory back from the

Allies in one go than ever before, some 12 miles in places,

as well as negate all the gains in territory, and losses in

men, that had happened to date.

They did eventually get to within 70 miles of Paris, close

enough to bring up several gigantic artillery pieces on a

railway that could throw a huge shell 80 miles. Indeed, when

Paris was shelled for a time, for several weeks, it seemed

as if we may well lose the war after all. Such views were

only reinforced by the fact that the same advances further

north brought the German army perilously close to the

Channel ports, of Dunkirk and Calais. It very nearly became

a 'rehearsal' for the very sort of advance that would

famously take place in those quarters some 21 years later.

As is the nature of these things, all these advances were

very costly in lives, our lives as well as German, and that

day was the start of a succession of events that made the

whole situation be couched in terms as per Wellington at

Waterloo - "it was a damned close run thing."

By the end of that week of the first push, matters were so

serious the government realised that a great number of

reinforcements were going to be needed in France if we were

even going to hold the Germans from further advances, let

alone turn the tables and win ground back. The expected

American divisions were still being formed and training, and

their help was some way off still. Urgent action was

required.

To that end, frantic orders went out to battalions in other

theatres, such as Salonika where we were fighting the

Bulgars, dubious allies of the Germans. In Egypt and

Palestine, whole battalions engaged in fighting the Turks,

the other main German ally, quickly embarked for the south

of France to be rushed by train across France and up to the

front.

In England, it was deemed so serious that the call went out

to call up to the colours all 'W' class reserves, even those

men previously thought to be indispensable in their civilian

work but who would now be most certainly required to fill

dead mens' shoes and plug some very serious gaps in the

line. First, Canadian regiments had come to the front in

1917, and now American battalions were appearing in ever

greater numbers, but not trained up enough or yet of any use

to thwart any further German advances. The hope had been

that more American divisions could be put into the line

before the Germans made a serious 'spring push'. The hope

was not fulfilled.

Everyone at home knew the Americans were coming, and no

doubt last-line reserves like Harry may have started to take

some comfort that they may not be required at the front

after all. But the Germans were also well aware that time

was running out for them, and they knew they had to make

their move before those divisions could arrive, or lose the

war.

The enemy attack that had started on the 21st had, a week

later on the 30th, been sufficiently consolidated to worry

the government enough to take such drastic action. History

books tell us now that the 30th was the day on which the

decision was made in Whitehall, to call up those last

reserves as well as bring any troops that could be spared

back from various parts of the empire and other theatres of

war. We really were in dire straights this time.

THE NORTHAMPTONSHIRES? NEVER !!

I never thought I'd see a document that so clearly ties in

with the dramatic events of that time, but there is one in

Harry's records. Referring to the date, 30 March, and the

official line and numerical reference of his original

mobilisation order that went out along with thousands of

others, it is also later stamped 12 April, presumably when

it was sent out again following the address mix-up.

The Royal Mail was nothing short of excellent in those days.

Letters bearing OHMS were always delivered the very next day

after posting. Assuming he received it on the 13th, Harry

seems to have had barely 6 days to inform his boss and get

his kit together. Also to get his train ticket, paid for

with the travel warrant enclosed, and say his goodbyes. He

was not going to France, not yet, he had some serious

training to do first. But his instructions also contained

bad news, for he was going to be transferred into another

regiment. After all his time with the Leicesters, and then

the Royal Defence Corps, he was now to transfer to the

Northamptonshire Regiment to do his fighting, and not be

with his mates and comrades at all. It was akin to asking a

man in a Yorkshire regiment to go to Lancaster and join the

Lancashires. The ignominy of it all.

So this really is his call to arms, finally, his 'papers'

had arrived, instructing him to report to regimental

battalion headquarters, in Northampton, for a medical in

less than a week's time, on 19 April. This was the letter

that had previously gone astray by being sent to a

non-existant address, and the authorities had finally caught

up with him.

Whatever his thoughts were, we've no idea. Having begun to

think he may yet be spared, he was now faced with the only

option open to him, to go and do his duty. It was what he

had once wanted, what he had trained to do. And now he was

needed, so badly needed, and it was his turn to go, to leave

his wife and two daughters, of 2˝ years and new born, and to

fight as he had been trained to do. As he prepared himself

and girded his loins to whatever horrors were to come, the

news from France simply got worse and worse.

We have to assume that, medical over, he did go home for a

time, though his papers don't indicate that. The next date

we have is 14 May 1918, the date of his official transfer

into the Northants, and the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion.

A day or so before he set off on his journey for his

medical, on 19th April, the Germans made yet another big

push, further to the south this time, and this was the one

that actually enabled the shelling of Paris. The news of yet

another major offensive would have hit the papers before he

set off. As it happened, serious as it was, it was not of

the scale and magnitude of the March offensive, but serious

nonetheless.

History tells us now that the enemy really were running out

of steam, both in men and materials, and in enough troops

still willing to fight. As well as our naval blockade really

beginning to bite, the collapse of the Eastern Front the

previous year theoretically should have released enough men

to make any German big pushes in the west a more assured

success. Had they been fit and willing troops for their

kaiser, it may well have been.

But German troops returning from Russia, where many had been

prisoners-of-war, had been 'indoctrinated' by their captors

in new Red Army of Lenin, and many of them never made it to

the Western Front at all, they literally deserted in their

thousands. A good many who did arrive at their new units in

the west arrived drunk. We have something to thank the

Bolsheviks for.

So each of those further two 'big pushes' were of less

potency than the first, and each ran out of steam just as

quickly.

His service record appears to suggest that Harry had been

'stood down' from parades or attendances at the RDC for

quite a while beforehand, perhaps on account of his mining

activities. I do recall reading that miners, in the First

War as in the Second, were not required to do Home Guard or

any firewatching duties, or any civil defence duties outside

of their normal mining shifts. Those shifts were deemed to

be hard enough without depriving men of much-needed sleep

and affecting badly needed output.

For curiously, his record has had an extra bit of filling

in, as an afterthought, dated after some later entries, that

states he 'rejoined' the 156 Protection Coy, RDC, on 13 May,

only to be transferred into the Northants the very next day.

He had to be 'in something' to be transferred out of it, an

administrative quirk to keep army records straight. The

inference has to be that he had been excused parades and RDC

duties for some time before.

Harry's instructions are then to report to the 3rd Battalion

to commence his further training, his service with the

Northants officially starting on 14 May. This was presumably

at battalion HQ in Northampton, where several hundred men

would be on garrison duties, involved in training recruits

and transfers and running the behind-the-scenes aspects of a

regiment at war. Harry was also re-numbered at this same

time, now becoming Pte Holt, 204379. By now there were 7

such Northants battalions, three of them on the Western

Front, and one still in the Middle East. Just a couple of

weeks after he started his training, yet another major

attack occurred in France, the third for three months in a

row.

We know this now to be the Germans' final gasp, on 26 May,

their last throw of the dice. It was expected, and in high

command quarters, almost welcomed, as it signalled the end

of the German army as a credible fighting force that could

win the war. A strategic victory to them in the short term,

it became a tactical loss in that it did ultimately end any

hopes of any further big pushes. They were spent.

Heavy merchant losses at sea to submarine attacks still

meant that we could lose the war, not by defeat of our

troops on land, but by starvation at home. Things were

critical, and the fear was we would have to sue for peace,

come to terms with the enemy, abandon both the French and

the Belgians, and withdraw our armies from France. Defeat,

on terms that the Germans would dictate.

Like the two previous offences, successful as they were in

taking territory and inflicting heavy casualties, this last

attack also petered out, ran out of steam and energy and for

many different reasons. Notably the length of supply lines,

but also because German soldiers were over-running

previously unoccupied areas and coming across country houses

and chateaux with wine cellars stacked to the very brim.

Undisciplined and in a euphoria of successful bloodlust, so

many German troops quickly became drunk, and as well as

other factors, that became one of the significant reasons

for all three final offensives failing. From then on, very

slowly at first, the tables would turn, and through the

summer whilst Harry learnt a new trade and got to grips with

a new regiment, a new weapon, and new mates plus all that

went with it, the tide of war really did start to turn in

our favour.

Harry's new trade may not have been his choice. He may well

have had it foisted on him, as a 'needs must' situation.

Presumably he was a good shot with a rifle, and also

presumably because his record tells us no differently, he

was an able and disciplined soldier. For he now trained as a

Lewis gunner, thereby earning a few coppers more per day

than the ordinary infantryman. But it was a deadly trade,

and just as our infantrymen and artillery actively sought

out German machine gun posts, so did the Germans to ours.

From now on, he was effectively a more of a 'marked man'

than he had previously been.

Because he was no longer an infantryman in the basic sense,

he was now also part of a relatively new team in modern

warfare, usually of five or seven men.

Previous machine guns were very heavy pieces of kit, mounted

on a tripod, just as heavy. They required a team to carry

gun, tripod, ammunition boxes and all the other

paraphernalia and be able to move and change positions

during the course of a battle. The Lewis gun, designed in

America but produced in huge numbers in Britain by the end

of the war, would now be Harry's main weapon. It would also

mean there would be no 'on the whistle over-the-top' deadly

charges towards a stream of enemy machine gun fire. For now

Harry was part of the team on our side covering our troops

as they went over the top and he would be directing such

deadly fire directly at German defenders, hopefully seeking

out their machine gun nests in order to neutralise them.

The skills and requirements, the fine arts of operating and

using a lethal machine gun, had been taught us by the

Germans themselves. They started the war with a great many

machine gun companies within their regiments. Our massive

casualty figures in those first years, through the

offensives on The Somme, and later at Ypres and

Paschendaele, were our instruction on how to kill large

numbers of men in the shortest time with maximum effect.

We were so slow to learn, most of our county regiments could

only muster but two such machine guns in any one battalion

at the start of the war.

In those early days, our weapons were also much inferior to

the very highly engineered, lethal weaponry then coming out

of German arms factories, of the likes of Krupp, etc. It

took us some time to design and produce in large numbers

designs that could be of their equal. The Lewis gun was the

best known and most successful of those designs in use by

the Allies.

By the time Harry was doing his training four years later,

most battalions had dozens of these newer Lewis guns, plus

we had our own Machine Gun Corps that specialised in this

new art of mass killing. A line of Lewis gun teams

interspersed along the front every couple of hundred yards

was now seen as de rigueur, and an essential part of any

battle plan, both for offensive and for defence. It's what

the enemy had been doing for 4 years, and we paid a very

heavy price learning those lessons.

To this

new arm, this deadly weapon that some believed had been

devised by the devil, Harry Holt now sought to learn it's

deadly ways and give of his best. To this

new arm, this deadly weapon that some believed had been

devised by the devil, Harry Holt now sought to learn it's

deadly ways and give of his best.

Through that summer, in general, the news from the front did

now improve. The expected American divisions slowly did

arrive. Canadian regiments were already in the thick

of it and giving massive support to the exhausted British

regiments holding what was a very thin line in places. The

French seemed to find new heart, and many changes had taken

place in how we, the allies, prosecuted the war. No longer

sending men to die in their hundreds to defend the

indefensible, we were getting canny, and learning a sort of

warfare that would be recognised today.

Those three German offensives petered out because we now

made tactical withdrawals to allow the enemy to get ahead of

himself, and run out of reinforcements and supplies. We gave

ground to give him enough rope to tactically hang himself,

and saved lives in so doing. We abandoned the dubious merits

of defending a trench to the last man. There had also been a

big change in the High Command, and not just American and

Canadians, but Australians and Indians too all gained

something of a reputation for fighting like tigers.

The two main big differences between the log-jam war of the

previous two years and now were the increasing use of

camouflage, and the movement of reinforcements up to the

front lines and forward areas only by night. Troops were

forbidden to move by day, and instructed to keep concealed

in woods and hedgerows, to deceive the increasing observancy

activity of the German air force. When we made a big attack,

the enemy now did not see it coming, whereas most of all

previous attacks, by both sides, the element of surprise was

given away by good intelligence gathering and observing

daytime troop movements.

As the summer wore on, Harry was presumably now at Aldershot

or Warley, huge training areas down south. A great number of

regiments passed through those garrison towns, and others

like Warminster and towns close to Salisbury Plain. July

turned to August, exactly 100 years ago as I first wrote up

this account, and August to September. But to backtrack

slightly, a major event was developing that in itself very

nearly cost us the war, though it had little to do with the

war itself. But it just may well have saved Harry's life.

June had seen the first UK outbreak of Spanish Flu. Slowly

taking hold, it progressed through more and more of the

civilian population, killing hundreds as it went. It was a

curious strain of flu, in that it did not so much take off

the very young or elderly, it struck at those most fit,

generally in a teenager to mid-30s bracket. Some seriously

fit and notable sportsmen, many serving in various regiments

would go down with flu one day, and be dead within another

two. It was all too common for several folks in one house to

die almost together, like an attack of the plague.

It hit the army hard, very hard, but it hit the navy even

harder. By August, the Admiralty reported several instances

of Channel Fleet destroyers not being able to put to sea as

convoy escorts simply because so many of their crews were

struck down. Several merchant ship losses were ascribed to

this temporary affliction within the fleet and lack of

protection against U-boats.

The disease spread, not only across this country, but right

across Europe, and by mid-summer, the War Office would

report to the prime minister that some parts of the front

line were so stricken by this sickness that the line was

held very thinly indeed. The fear was that if the Germans

could have mounted just one more concerted attack in force,

they would have broken through once and for all, especially

if that breakthrough was towards the channel ports, always

their intention for four years anyway. But, the flu struck

them as well, even harder, on account of the by now very

poor nutrition of their troops. It would turn out that the

enemy had spent their last and best efforts in May. But of

course, our forces didn't know that then.

September would see Harry and his new mates guessing that

their period of training, just less than 5 months, was

coming to an end, and it would soon be time to go to it.

When his time came, events must have seemed to take on a

life of their own, and as is the way with army life after

months of training and a certain amount of boredom, things

start to happen in a bit of a rush, almost a whirl.

The first thing was his transfer to the 6th Battalion,

officially on 23 September, a nominal transfer only because

at that time, the 6th had been fighting in France since the

previous year and still were. They had sustained enormous

losses already and fought their way through many of the

notable battles that later became bywords of bravery and

endurance in British history.

After each action, all battalions would replace their losses

once they were relieved at the front with a supply of new

and fresh drafts of men sent from the two Infantry Base

Depots at Calais or Étaples, both near to the French coast.

Some men would be returning from sickness and wound

recuperation, and others would be raw new recruits, barely

18 years old and fresh out of training.

A cross-channel military ferry service, guarded by

destroyers of the fleet, maintained a constant to-ing and

fro-ing, bringing reinforcements to France and taking sick

and wounded back. In those final days of 1918, from the

summer onwards, the amount of that traffic and sheer numbers

of men became almost frenetic, an organised chaos. It is now

a known fact, not realised then quite so readily, though

many in high places would have suspected it, that we lost

more men killed and wounded in 1918 than in either of the

previous two years of the war. Notwithstanding those huge

losses at the famous actions on The Somme and at Ypres,

Cambrai, Amiens and others, the combined totals for the

smaller actions in 1918 alone would exceed them.

The three big final German spring pushes had accounted for

much of it, but now, with the Germans starting to be on the

run, and the flu taking its toll making manning matters much

worse and so yet even more casualties in battle as a result,

the figures were truly nothing short of horrendous.

What is notable is the number of older men amongst them,

those well over 30, sometimes up to their late 40s, married

men with several kids, who were sent to fight in those final

months when desperate measures required desperate means and

who did their duty but still succumbed to bullet or shell,

if not the flu.

TO FRANCE - AT LAST !

It is 24 September that sees Harry move closer to France.

First at another Northants transit and training camp on the

Isle of Sheppey, known as Scrapgate Camp, where his medical

the previous day unsurprisingly pronounces him 'A1 Fit' for

service abroad. From where he then travels to Dover to

embark, along with many other men also being posted to the

front, on a ship to France. He lands at Calais the very same

day, to find himself in no time aboard transport, perhaps a

lorry or train, en route to the IBD, the infamous Infantry

Base Depot, at Étaples, some 32 miles to the south, arriving

by that same night.

He had arrived. Harry was in France. After almost four years

of waiting, and reflecting that at one time, he had really

wanted this, he must have spent his first night feeling very

lonely and distant in this gigantic camp of tents and wooden

huts. Essentially a transit camp, an IBD is a human

distribution centre for want of a better description,

designed to hold men awaiting instructions for further

postings. This is where they were billeted in huge barrack

blocks, so slept, fed and watered and re-equipped whilst

they were allocated to a regiment, or awaited transport to

one they were already posted to. The 24th is also the

official day he becomes part of the 6th Battalion, but still

Harry is still a long way from it. He is re-badged, with a

new cap badge, displaying the triple castle turrets and

battle honour legend above, 'Gibraltar', of the

Northamptonshire Regiment.

The next entry, 29 September, he finally joins his regiment,

his unit, 'in the field'. This suggests he spent at least 3

or 4 days kicking his heels, along with other reinforcements

bound for the same destination. He would have no idea where

he was going, and I doubt at that time he knew the names of

very many French places, other than Paris and the famous

channel ports he had just passed through. Some names on the

Western Front had gained fame through newspaper reports. If

he had been keeping up with those, he may have noted the

name Saint-Quentin amongst all the others like Bapaume, and

Cambrai, famous for its recent tank battle.

News may have come through on the ubiquitous grapevine about

a huge action at Saint-Quentin, of a famous battle to cross

the wide canal there against massive German opposition, but

he may not have known then that was the site of one of the

6th Northants' most recent actions. He would a day or so

later when he finally caught up with them, at a little

village called Nurlu, well behind the then front line.

In actual fact, what I believe he caught up with were the

'battalion extras', at Nurlu, as stated in the recently

discovered battalion diary. For as the diary also makes

clear, the main body of the battalion itself was still in

action, to the north and east, and involved in some very

heavy fighting as they chased the Germans further and

further back and were not relieved for another couple of

days.

Something I hadn't realised until doing the most recent

research was that, when a battalion went into action, or up

to the front lines, they usually left behind the 'battalion

extras', which was a cadré of a few dozen officers and men,

experienced NCOs, and some admin staff, at a safe place

behind the lines. These were intended to rebuild the

battalion in the case of such severe casualties it had been

effectively wiped out.

This happened in very many cases, for there are dozens of

instances of so few men returning from an action that a

whole battalion of some 800 to a 1,000 men, effectively

ceased to exist. Hundreds may take part in an advance from

which barely small dozens would return. In such cases, they

may be merged with another badly mauled battalion, and it

was the job of the 'extras' to arrange for reinforcements,

order replacement equipment and munitions, and train the new

men for their new duties and rebuild damaged battalions.

It could take three weeks to a month for such a depleted

battalion to be rebuilt to a strength and ability enough to

go back into the line. I believe that Harry arrived at such

a time, when the battalion was about to be relieved and

return the the rear areas to rest and re-equip, and to

receive more men, such as Harry.

At 4am on the 29th, when Harry was probably travelling east

to Nurlu, the battalion was actually forming up on a start

line to go into action again about 5 miles to the east, very

near to Lempire and a farm noted in the diary as TOMBOYS

farm - an English spelling, as it is actually Le Tombois.

The farm is still there.

At 5.30, the battalion advanced 'behind Americans', the

diary says, with A and D Companies in the front line, and B

and C in reserve. They advanced slowly north-east all that

and the next day across the fields for a mile or so, to just

south-west of Vendhuile, taking yet some more casualties.

The diary talks of confusion caused by a 'smoke barrage' -

ours or the Germans, we don't know - and mentions 8 officers

wounded, including the company commanders of B and D

companies.

Brigade instructions had been to cross the canal at

Vendhuile, but fierce enemy machine gun fire had forced that

order to be abandoned, and the battalion dug in just west of

the town, but taking command of one of the canal bridges.

The fighting died down overnight, presumably because the

Germans did as they were always doing by now, packing up

their kit and legging it off into the night. It was here,

the next morning, they were 'relieved by the E. Surreys

after a very strenuous period'.

It was now October 1st, and the battalion then marched a

couple of miles to the west, back to some old trenches at

Ronnsay Wood, scene of a ferocious action only a few days

previously. Here they rested and regrouped, and it is here

that I believe Harry - along with other reinforcements -

most likely joined his new unit properly, literally 'in the

field'.

It is not too much a stretch of imagination to see them form

up into twos and march eastwards out of the camp at Nurlu

but four miles or so along the remains of country lanes,

such as they were by then, and by way of a couple of other

villages to join the main body resting at Ronnsay. From

herein, Harry's war started in earnest, and he would have

been forgiven for thinking that it was going to be a long,

long time before he saw the English Channel again.

We have to remember that, at that point, on October 1st

1918, a great many folk thought the war still long from

over. It was assumed by most that the Germans would have to

be chased, yard by yard, mile by mile, right back into their

own homeland before they would ever give it up and admit

defeat. Some in higher positions, a lot of senior officers,

sensed that an end was coming, but few would have put bets

on it being so close, and certainly not before Christmas.

Most soldiers in the line still believed it would be well

into 1919 before victory could be claimed. And of course, no

one knew just how it would end, with yet more massive

do-or-die battles, or a near stalemate, an outright victory,

or what. As close as we seemed to be to victory on the

Western Front, losses at sea could still decide the war in

the enemy's favour, and it would be they who would dictate

the terms. The balance was so fine.

But it was not to be immediate action for Harry. The

battalion had come out of the line, and would now get

transported, on presumably open backed lorries, though the

diary poetically terms it 'embussed', to take them many

miles to the west, well back from the present front line to

even better billets just north-east of Amiens, at

Molliens-au-Bois.

Perhaps they did use buses, primitive French-style

charabancs as well as lorries. They went back almost

directly west, traversing all the old battlefields and

criss-crossing many old front lines. That journey in itself,

to a very attentive newcomer to the war, would have been an

eye-opener indeed, a sort of impromtu live 'battlefield

tour'.

The fronts were still not all that far away, and the rumble

of distant artillery gunfire would occasionally be heard. At

night, the skyline to the north and east would be alight

with flares and occasional explosions of shells in the far

distance.

But though they were still well to the north of the old

battlefields of the Somme itself, it was a dispiriting

journey west through wrecked villages, along badly

shell-pocked lanes with barely any green or fresh growth of

anything to be seen. What could be seen would be heaps of

turned earth, littered with the remains of rusting barbed

wire, abandoned guns and kit, occasionally a wrecked newly

fangled tank, as they passed columns of troops marching the

other way to the front and units of military police at every

road junction directing traffic. Despite increasing

mechanisation, still to be seen would be an enormous number

of horses, mostly pulling supply and ammunition carts, and

of course, field guns of every size.

It was some 40 miles of unbridled destruction, the most

notable of which he almost certainly passed through was the

totally destroyed town of Albert. Hardly a brick or stone

left standing one above the other.

On arriving at Molliens-au-Bois, a camp of considerable more

comfort than had been enjoyed of late, though apparently

Nurlu wasn't so bad, Harry spent the next 14 days. He was

technically all ready and fit for battle, but his new

comrades newly returned from the fight now rested, bathed,

replaced lost or damaged kit, and generally relaxed. Harry

would have quickly been introduced to his gun team, or what

was left of them after their recent action. He would have

then heard his first real tales of battle, not third-hand or

hearsay from a long way away, or read in newspapers, but

first hand accounts by the men who were there.

The diary tells of a period of intense training to start

with, re-equipping, plus battalion inspections by the

Commanding Officer. The 6 October was a Sunday, and a

planned church parade was cancelled owing to no chaplain

being available. No doubt there were times they were also in

short supply, and doing more gruesome duties elsewhere.

From the 10th, there were many more lighter moments in camp,

notably inter-regimental and inter-divisional football

matches. On that day, 6/Northants drew two-all with the

11/Royal Fusiliers. The next day, they lost 4-0 to the

2/Bedfordshires.

The 12th is almost lighthearted, a Brigade Sports Day, and

Lt-Col. Turner in writing up the diary - our bits are all in

his scrawling hand throughout - he writes, 'Joy Day.'

We can only speculate and wonder in how much of this Harry

took part. It would have seemed odd to have come so far to

end up playing sports and football. The 13th may have been

even more joyous; this time, there was both a church parade

and a major inspection by the GOC Brigade. Followed by yet

another match, a return game against the 11/Royal Fusiliers,

and this time they thrashed them 5-1. Oh what joy!

But underlining all that 'joy', all troops would have known

they were only preparing and girding themselves to be sent

back into the fight. Including Harry. Just another couple of

days now. There was serious work to be done.

"ADMIN INFLUE" :

On the 15th, the battalion received instruction on

'Protection on The March', and 'Outpost Duty'. The following

day, transport arrived, and the whole battalion 'bussed it'

back to Nurlu, a first move back in the direction of the

fighting to relieve another battalion, and so the cycle

began all over again. In and out of the line, as the

6/Northants had been for much of the war, frequently with

many men just as fresh to battle as Harry now was.

But not Harry. It is my belief he perhaps began to feel ill

even on the 14th, when on the final day of the Brigade

Football competition, they got their revenge and beat the

2/Bedfords 1-nil. I do wonder if Harry was already very

off-colour by then.

For on the 15th, his own records state: 'To Hospital', and

place given, 'in the field'. The next entry is the same day,

also on the 15th, to 54th Field Ambulance, 'Admin Influe'.

Harry was out of it, and to date, had never fired a shot,

not in anger anyway. And it was now looking as if he never

would.

So it would be Spanish Flu that saved him from going with

the battalion the next day as they went back to the front,

and perhaps even worse, we'll never know.

As the battalion shipped out one way, Harry was almost

certainly on a stretcher in a covered ambulance going the

other. This time to the 41st Stationery Hospital at Amiens,

which in fact was the former big town civilian hospital and

so far as I know, still is.

Eight days there saw a good deal of recovery. He was indeed

a very lucky man. Some battalions had a higher death rate

than others, it was never universal. To make an average,

which is meaningless really, some battalions hardly lost a

man, others had so many afflicted they were effectively of

no use for several weeks, with a death rate worse than that

in battle at that time. Significantly, Harry's Northants

battalion appear to make no mention of this epidemic in the

war diary. First impression has to be they didn't have that

many.

However bad he had it, and however soon they caught it, it

was Amiens that saved him and started to put him to rights.

The next move was to the coast, to Le Tréport, to the 16th

General Hospital, where he spent about a fortnight. He must

surely now have been on the road to recovery and felt a good

deal better. That flu either took you quick, or not at all,

but recovery was a long time.

His final move was to the 3rd Canadian Hospital, then at

Dannes-Camiers, again not far from the coast. All these

military hospitals can be researched and appear on various

WW1 websites, but care must be taken to note the dates, as

they moved around considerably, but they are now all

'findable' online. They may be designated 'Stationary'

hospitals, but they were anything but that. No41 quoted

above was in five different places during the course of the

war, finally ending up in Germany for the occupation.

The move from Le Tréport to Dannes-Camiers was at least in

the right direction, from the army's point of view, as it

was clear they wanted him back. Due west across the channel

may have been Harry's preferred direction, but it was not to

be. The 3/Canadian Hospital was just north of the IBD at

Étaples, and it is to there that he was sent on 8 November.

He remained there until the 15th November, so there we have

it. Armistice Day, the end of it all, would be spent in

contemplation if not celebration, in a Canadian-staffed

hospital miles from the front, and miles from home.

Contemplating his luck, or lack of it, for he had never

fired a shot in anger.

For many, celebration was too strong a word, especially

those still 'in theatre', those in the battlefields, whether

soldiers, admin, medics or whatever. There were joyous

celebrations at home, often deliriously so and well OTT, but

many celebrations were still rather muted when folks paused

and remembered the huge cost of this dubious victory. I

think whether one celebrated or not was directly linked to

how many of your own family had been lost in the carnage.

Some men at home celebrated because it almost certainly

removed the immediate possibility of call-up, or at least of

being shot at. But it was not all fun and games for

everyone.

When he was first admitted to hospital in mid-October, even

then the end wasn't really thought to be quite so close.

Having come through the flu and starting to recover,

realising he had not died after all, Harry may even then

have hankered after getting back to his unit and fearing it

would all be over before he got there. Or maybe not. Maybe

he regarded it as God's blessing and could now be a little

more reassured he would be returning home to his family -

one day.

Because of his illness, at least two of three days of which

he would be almost in a coma, out of it, and then the

repeated moves from one hospital to the next, it would all

have seemed something of a whirlwind. As he recovered, and

heard the tragic tales of others that had not survived, deep

regrets and negative feelings almost certainly set in. He

was a quiet man in old age, contemplative, slow to anger,

but as my mum often recounted, when he was riled, everyone

knew about it. Slow volcanos often go off with the biggest

of bangs.

And now, with recovery, the whirlwind was not over. It was

back to the base depot to await transport to rejoin his

unit. Not fighting now, but heavily involved in what must

have been the biggest 'clear up' in history. He didn't kick

his heels long at IBD this time, a day or so, for on the

17th he was back across France at his Battalion rest centre.

The 19th saw him back 'in the field', after a second

journey, not a bit comfortable at a guess, back across the

war-torn battlefields.

And what a 'field' it must have been. The diary tells us,

after nearly a fortnight's final heavy fighting up to the

11th, the 6/Northants ended up near Le Cateau, not so very

far from Ronnsay Wood and Epephy close to where he'd joined

them the first time. Back on the 4th and 5th November, they

went through a particularly bad time, in the actions at

Eppinette Farm. Three officers were wounded, 15 other ranks

were killed and 96 wounded, and one man was posted missing

entirely.

So close to the very end, men were still being lost in some

numbers. But, even on the 5th, although there was much talk

that it was nearly all over, as the grapevine and rumour

mill abounded with stories that German commanders had met

with French and British to seek terms, there was still no

confirmation at battalion levels.

Harry rejoined 6/Northants on 17 November, to what must have

been a very different atmosphere. A mixture of huge relief,

almost shock, perhaps even disbelief, as well as a sort of

childish euphoria still remaining amongst many. Now, there

was a lot of work to be done, but at least it wasn't

killing. Or being killed. Most of that initial euphoria at

such an unexpected victory would by now have passed amongst

most fighting men still out there. The biggest and most oft

asked question on most soldiers' lips was -'when are we

going home?'. For some, quite soon, but for now, there was

work to be done, some serious 'tidying up', a great deal of

it not at all pleasant and very likely to leave a sensitive

man with nightmares years later.

The diary is now very bland and matter of fact for the next

month or so, telling of the battalion involved in filling

trenches and shell holes around their villages, a great deal

of salvage work which covers everything from gathering up

masses of barbed wire to shell and cartridge cases by the

ton, to removing what was now scrap metal in all its forms,

damaged and wrecked guns, limbers, carts and all the

material of an army in the field. Diary entries don't

specify what 'salvage work' and clearing up entailed in

detail, but there can be no doubt that it would have

frequently been a most gruesome task. One job noted was to

'remove all evidence of German occupation' for the

villagers. I'd like to think our lads were very welcome, and

treated like the gentlemen they very much were, as well as

liberators.

Another task that befell some was the re-burying of the

dead, finding the more recent hurried graves on the

battlefield, and exhuming the bodies to be taken to the

larger cemeteries then just starting to be created.

Such work had to be very heavily documented as they

progressed, no detail missed, every man recorded where

known, and what details as could be ascertained via cap and

shoulder badges where the name wasn't known. German as

well as British or Allies, every dead man had to be recorded

and typed records sent back to London, or liaised with their

former enemies in the German army. I think Harry may

well have escaped the worst of that too, but he would have

known, heard, just what strong stomachs it took to exhume

and rebury so many dismembered and rotting corpses.

The next more interesting entries are mid-December, when

Lt-Col Turner's handwritten account seems to take on a more

visibly cheerful note. His handwriting gets a bit larger and

more floral, as he tells of preparations of billets and

recreation rooms within camp for the looming Christmas

period. There are church parades, and inspections, and I

daresay men chafed at that, but an army is an army, and

needs to keep fit and sharp and on the ball. There was

always the danger the armistice might fail, and some more

hard-lined German commanders may gather enough troops for it

to all kick off again. The 6/Northants were lucky in that

they stayed roughly where they were when hostilities ceased,

in the Walincourt, Malincourt and Élincourt area. These were

the main focus of daily work parties to clean up the

villages and help the inhabitants in their first steps along

a long road to some sort of normality.

December 23 is marked as a 'start of the Christmas holiday',

and undoubtedly there would be a great clammering for leave,

but not always granted. I'd like to think that Harry had

some sort of a clue as to his early demob when he returned

from his sickness the month before and may even have

entertained hopes of being home for Christmas.

The first he may have heard, could have been on the 17th

when he got back to the battalion and perhaps wondering what

he had to do next. History books tell us now that our High

Command had indeed some considerable prior knowledge that

the end was near. For several weeks, intelligence reports

were telling that the German army was so near to collapse

that it seemed unlikely they could fight on even until the

end of the year. Enemy generals had been making moves since

mid-October to ask for terms to end it. Given that

knowledge, preparations had been in hand for some time to

arrange for coal miners to be returned just as soon as the

last shot was fired. But of course, neither Harry nor any of

his mates were aware of any of that at the time. On the day

that Harry got back, some sarcy NCO might well have turned

round and said, "you're going to be alright, Holt, you lucky

sod, you're going home! Miners are being returned first."

HOME ?

And indeed they were, and the guns had barely fell silent

before the first of those orders were being sent from London

to brigades and battalions everywhere. The pits at home were

in a real crisis, the winter hard, and folks were literally

freezing for want of coal. And of course, the shortages were

hitting industry badly too.

But many of the demob instructions were not popular, neither

with the men nor some of their officers. There was a great

deal of disquiet in a lot of divisions, and almost mutiny in

a few. After miners, the next main group were described as

'pivotal men', which encompassed every sort of trade and

skill that had been robbed mercilessly to provide troops to

fight the war. Naturally, the men that had volunteered

first, before the days of conscription in 1916, expected to

demob first, but in many cases it didn't work out that way.

I sense that Harry, envied and considered lucky by his

messmates, may have attracted not a little jealous sarcasm

in his last weeks of service.

We know nothing of how he spent Christmas, but it was not at

home. He was now a member of 'A' Company, and the diary

tells that B and D companies had their Christmas dinner,

served by officers, at 1300hrs on the 25th. A and C

companies had to wait for theirs until Boxing Day. If he

didn't know already as he had his dinner, he would have done

the next day for sure. His records state that on the 29th,

he was 'transferred to England for release from the army for

coal mining.'

It seems he was back in England for New Year's Day, but not

yet in the bosom of his family. His soldier's Protection

Certificate and Certificate of Identity (for soldiers not

remaining with the colours) is dated Jan 5th at Talavera

Barracks at Aldershot. His place of rejoining in an

emergency is given as Purfleet, and trade as L.G.

His record, and that certificate, shows he was given 28 days

leave, and officially left the colours on 2 Feb 1919. But I

think he was finally home by the 6th Jan, and back at work

easily within a few days. When he entered the lift cage to

go underground for the first time in almost a year, he must

have pinched himself and thought, did I do all that.

He was still regarded as a soldier, only being released to

Class 'W' Reserve, and Lt-Col Turner has signed the official

form, 'Release from the army for coal mining (overseas)'. So

England was 'overseas', was it. Very good, no matter.

I felt a bit sorry for Col Turner as I reached the end of

this narrative. He was obviously approaching elderly status,

if not already 60 then not far off, looking at photos of him

in the archives with his big bushy, white mousetache. He had

taken a wound, from a shell, the previous year when in

command of the Royal Fusiliers, and earlier in 1918 had been

away from the battalion for a few months. He in fact

rejoined in September, just before Harry arrived. Turner

must have known, as would all elderly and long-overdue for

retirement officers would have known, that the end of the

war was the end of life as they knew it. Not every officer,

or man, so quickly retired, had the foggiest idea what they

were going to do with themselves. Not all had a career or

means of employment to support themselves if still aged

under 65. Life was very tough, for hundreds of

thousands of men of all ranks suddenly thrown to the

vagaries of the winds of civilian life.

In the event, Col Turner left before Harry did. The diary,

filled in by his own hand in scrawling pencil as usual,

states at date 2 Jan 1919 ... 'Lt-Col Turner left the

battalion.' And that was that. A major took charge for the

next couple of months until the 6th Battalion was finally

disbanded in April. They had gained some considerable battle

honours, been involved in endless heroic fights and suffered

huge numbers of casualties. Harry had joined them almost

right at the end, and had been spared the worst of the

horrors his predecessors had had to go through - by simply

having the flu.

I have no doubt that Harry was proud of his army service, as

witnessed by the continued presence of his picture hanging

on the wall above the sideboard until the day he died. I've

no doubt Violetta, and in time, his four daughters were

proud of him too. I can also state with some certainty that

he was a patriot, a loyal subject of his king, and didn't

subscribe to the later condemnations of Great War leaders,

like Haig and Lloyd-George, who were later belittled as mass

murderers.

How do we know. Purely from the graphics around his image,

images of the king and some of those war leaders. He would

not have left them there if he had agreed with such views,

and would surely have had the picture removed from its

patriotic, flag-bedecked mount even if it was then rehung

plainly in the living room.

CONCLUSIONS :

I'm also sure Harry was a socialist, with a relatively

small 's', and of course, a member of the miner's union.

There may seem to be some conflict, an anomoly, with all

those viewpoints. Moreover, he was very religious, of the

Methodist/Salvationist persuasion, and all the more so

after the war as he tried to come to terms with what

little he had seen of it. For some men, experiences of war

drives religion and faith clean out of them. For Harry, it

seems to have strengthened them, and perhaps an increasing

faith is what helped carry him through those dark days,

years later in the 1930s, when we know he had nervous

breakdowns and more than one stay at the miners'

convalescant home at Cromer. Life was a constant struggle,

even on miner's pay. It's what all the arguments and

strikes and constant strife with pit bosses and later

governments were all about.

Life was very tough through the 1920s by our cossetted

standards of today, and if a lot of men who returned from

the war had little or no political views when they went to

war, they certainly developed strong ones in the two

decades after. Two more daughters would be his and

Violetta's blessing, Mavis in 1923, and Sylvia my mum, a

full 7 years later in 1930. By the time Sylvia was born,

Gladys was 14 and already about to move away, to

Loughborough, 'in service' to a wealthy baker's family.

All of this story could never have been told as full as it

has been without first gaining access to Harry's service

record. Moreover, not only access, but being able to